This text has been submitted as an original contribution to cinetext on July 18, 2003. It is also available as PDF-document for high quality printing.

Alain Resnais and Atom Egoyan

|

|

by Crissa-Jean Chappell |

In the hypnotic films of the Canadian auteur, Atom Egoyan, voyeurism lurks everywhere, cataloguing existence, replicating reality, reducing human beings to digital fragments. He fills his minimal scripts with visual metaphors and carries them from one work to the next, often using technology to create a cold, calculated ambiance. Egoyan, much like Resnais, forces viewers to approach his films like detectives, piecing the narrative from broken fragments. In certain ways, Egoyan takes Resnais’s concerns further — or brings them up to date. On the other hand, Egoyan’s work doesn’t seem to have the focus on literature, or on the relationship between cinema and literature. Instead, Egoyan focuses on television and other media.

Hiroshima, Mon Amour opens with bodies covered in sand. These images are both beautiful and deformed, already suggesting the dual nature of the film. Their hands are like stone statues, immortalized in lovemaking. In the following sequence, photographs of Hiroshima’s hands are placed in a museum as a reminder of the nuclear explosion. We see a powerful juxtaposition of the present-day lovers with the devastation of Hiroshima fourteen years earlier.

A similar moment takes place in Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter. The opening frames of the film show a simple shot of domestic bliss: Mitchell’s wife and daughter in happier times, sleeping peacefully in the same bed.

The Sweet Hereafter (Alliance/New Line, 1997).

During his conversation with Allison, his daughter’s childhood friend, Mitchell recounts the story of how Zoe almost died from a spider bite, and how he was willing to slice her throat open with a pen knife should her throat close and prevent her from breathing. Mitchell’s painful memory is scattered throughout the film as a visual complement to the town’s present-day tragedy.

The Sweet Hereafter (Alliance/New Line, 1997).

These moments from Hiroshima, Mon Amour and The Sweet Hereafter exemplify a radical departure from traditional cinema, dominated by space and movement, in favor of a cinema centered on time — the radical transformation of cinema that Gilles Deleuze advocates in his books Cinema 1: The Movement Image and Cinema 2: The Time Image. Resnais and Egoyan both recognize fundamental inadequacies of the image as a substitute for memory, although much of their work is an experiment in exposing those inadequacies.

Deleuze's notion of time-image cinema describes a revolutionary and political cinema. To understand time-image cinema, we must contrast it with movement-image cinema, "in which frame follows frame according to necessities of action, subordinating time to movement."[1] Resnais and Egoyan’s work is nothing like movement-image cinema. Their films have little action or plot that could subordinate time. Instead, their images may trigger gaps in time and logic, forcing the viewer into becoming part of the narrative process. Much of their work is about what could be described as the technologies of memory and the ways individuals are lost within the process of trying to record or assimilate memory.

Egoyan has included a photographic device in almost every film he has ever made, from Speaking Parts, in which all the characters project their feelings, dreams and impressions of other people in video, to Felicia’s Journey, where the "catering manager" obsessively watches a cooking show hosted by his mother on a small, black-and-white television. Resnais’s Hiroshima, Mon Amour also makes use of technology and recording. The grisly photographs in the war museum do not seem to match the love scene and work against the illusion of watching a dramatic scene. The naked bodies become an emblem of life against the symbols of death in the documentary footage of Hiroshima’s holocaust.

As these films explore the relationship between memory and recording, they support the image of time described by Deleuze.

Deleuze proffers an image of time as always splitting, like a hair, into two parts: the time that moves smoothly forward, or the 'present that passes'; and the time that is seized and represented (if only mentally), or the 'past that is preserved'. What Deleuze, following Bergson, refers to as the actual image and the virtual image are the two aspects of time as it splits, the actual corresponding to the present that passes, the virtual to the past that is preserved.[2]

A central theme in the films of Resnais and Egoyan is the inadequacy of memory. For example, in Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad, the man, X, tries to persuade A that they have met before. In a series of shots, we see different explanations that give rise to speculations about memory, ending with the shattering glass that ties into other events in the film. As X tries to give concrete evidence of their affair, he mixes up the details. At first, he sees A standing in a black dress. Then he sees her in a white dress, poised in the same posture. Later, he combines the posture in the white dress with the white statue and imagines her by the banister. These alternating details might suggest the gradual shape of X’s memories.

Egoyan’s Exotica also presents a potent sense of the past’s grip on the present. Francis’s loss of family causes him to recreate or purge the past by playing protective father to a stripper who masquerades as a schoolgirl during her act. He continues to pay his babysitter to watch over an empty house. When we see his home-video footage of better times, with his wife and daughter smiling for the camera, the impact is reinforced when the woman blocks the lens with her hand, blocking our view and claiming the memory.

Exotica (Alliance/Miramax, 1995).

These films deny that images are a solution to the memory problem. Resnais and Egoyan show us that preserving the past is also problematic. As Deleuze proposed, they demonstrate how our virtual (filmic and photographic) images compete with our "recollection images" — our memories of events not captured in film and video.

B.C. Holmes’s essay on Deleuzian Memory presents six "inadequacies of memory" that are easily applied to the works of Resnais and Egoyan. The first inadequacy says the past that is preserved equals only half of time — the present that passes is not really captured along with those images. The sense of time in classical cinema is only indirectly implied through montage. Deleuze writes that traditional cinema (movement image) has

"…two sides, one in relation to objects whose relative position it varies, the other in relation to a whole — of which it expresses an absolute change. The positions are in space, but the whole that changes is in time. If the movement-image is assimilated to the shot, we call framing the first facet of the shot turned towards objects, and montage the other facet turned towards the whole… [It] is montage itself which constitutes the whole, and thus gives us the image of time… [But] time is necessarily an indirect representation because it flows from the montage which links one movement-image to another." [3]

The break between images is usually ignored. When the French woman in Hiroshima, Mon Amour says that she knows everything in Hiroshima, the Japanese man rejects her statement. Resnais compares the two rivers; the girl whose head is shaved and the Japanese women whose hair falls out; the human skin of the war museum and the bleeding fingers of Nevers; the dead soldier’s hand and the twitching hand of her Japanese lover. We can try to reconstruct the "whole" picture of the past, but the true picture has already faded. The break Resnais introduces between the city before and after the war (and the woman’s horrific experience in Nevers) cannot be ignored.

A similar example is found in Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter. When we first see the peaceful family triptych that opens the film, we can’t connect it to the present-day events in the narrative, nor the people who have lost their children in the bus accident. Later, as Mitchell claims the memory as his own, we can identify the young father as the gray-haired lawyer and the baby as his drug-addled daughter. Egoyan forces us to look at the two moments and recognize the present that passes.

This leads to the second inadequacy: some moments are too ethereal to be recorded. For example, in Calendar, Egoyan's photographer takes pictures of the Armenian churches but cannot capture their history. The French woman in Hiroshima finds it difficult to articulate the deep, private complexity of her horror in Nevers. It becomes a statement about the privacy of stream-of-consciousness and her inability to externalize it.[4] When the Japanese man asks how long she spent in the cellar, she says, "Eternity." This sense of timelessness cannot be expressed in words.

A third failing of memory concerns the imperfect interpretation of images from the past. The characters in Egoyan and Resnais’s fractured narratives do not remember. They rewrite history, much as history is rewritten. Egoyan’s Family Viewing is about a young man who finds that his father has erased their home movies with strange footage of his own sexual experiments. Much like X in Last Year at Marienbad, the distant father stamps out his recollections of a former relationship. The son defies his father's authority in an effort to preserve his memories of his mother. The stepmother tries to explain by saying, "He likes to record." The boy responds, "He prefers to erase."

It would be impossible to look for only those images that are true. Egoyan, like the French New Wave filmmakers, tries to show that home movies and other ‘public’ images comprise a sort of official history, while the unpreserved present is more like unofficial history or private memory.

This leads to the fourth failing of the image: official histories don't just inform a culture, but also shape their communal identity. The war relics in the Hiroshima museum have become part of our collective unconscious. As impersonal objects, they have almost lost all meaning. But the Japanese man only has to hear the river to remember the sound of acid rain falling on his people. When the French woman hears water, she remembers the stream in Nevers.

The fifth issue reveals how official histories force out other images.In Hiroshima, the French woman grows upset when she begins to forget her German lover’s face. She says into the mirror:

"I told our story. I was unfaithful tonight with this stranger. It was, you see, a story that could be told. For fourteen years, I hadn't found…the taste of impossible love. Since Nevers. Look how I am forgetting you… Look how I have forgotten you."[5]

The collective nightmare of the war, recorded as an official history in museums and documentaries, is beginning to eclipse the woman’s personal memories. Unlike the girl, the Japanese man lives in Hiroshima. The past has become entwined with his present-day life. The official history doesn’t have the same devastating effect on him.

The Sweet Hereafter, Mitchell, the manipulative lawyer, tries to shape an official history of the town’s personal tragedy. He twists the facts in attempt to find someone to blame for the bus accident. But his lawsuit cannot bring the children back, nor can it alleviate his own helpless feelings toward his drug-addicted daughter, Zoe. When he videotapes the mangled bus, its rusted parts reveal nothing. The footage of the bus can never be anything more than images.

The ability to empty an image leads to the sixth issue: all images have the capacity to deceive. Exotica concerns the exoticism we feel toward our own experiences, and the point at which our memories seem foreign. At first, the videotape of Francis’ ex-wife and daughter seems peculiar because we can’t place it into the context of the narrative. Egoyan says:

"Even that footage is so interesting, because when we first see it, we think it's a threatening moment, that the mother is protecting the daughter. But in fact, it's this happy, playful moment, but Francis has fetishized it, and taken it out of context, in order to give meaning or explanation to his anguish. I think that's one of the more interesting things that's evolved [with video technology], our newfound desire to make archives of our experiences, and to document them. For all of the potentially healing aspects of that, it also poses a danger, because our memories that are able to change organically, to position themselves within who we become, but technology is fixed. So the images have to be reconfigured in more brutal terms."[6]

In Resnais’s Holocaust documentary, Night and Fog, the concentration camp in Auschwitz was shot as it looked at the present time, using color film. This contrasted with the blurred and scratchy newsreels and photographs of the past. Except for the barbed wire, the camp looked like a typical stretch of Polish countryside. "Weeds have grown where prisoners walked." No matter how hard we try to imagine the misery of life there, we cannot recollect it. "Only the husk and the shade remain." The river, "a water as sluggish as our memory" flows away. By contrasting the Nazi’s actual footage of horror with peaceful shots of Auschwitz in the present, Resnais shows the effect of time on human memory. Even the camps themselves were a euphemism. They were provided with hospitals and a train service. But the hospitals allowed their patients to starve to death. And the trains never brought the people back home.[7]

Egoyan's obsessive voyeurism explores the connections between individuals and dehumanizing media. Exotica, Egoyan's first commercial hit, investigated a group of isolated characters who share common experiences but remember them differently. As in all of Egoyan's alluring films, the plot ricochets back and forth between time, heightening the atmosphere, allowing links between characters to develop slowly. Egoyan never explains enough to dissolve the mysteries. We see men ogling topless dancers in a smoky strip club, a luminous field speckled by people searching for a dead body, fishtanks gurgling in a dimly-lit pet store. The narrative increases intensity, moving at a minimum, gradually exposing variations on a theme. Even as the viewer puts together the pieces, they can never be sure of their authenticity.

Exotica (Alliance/Miramax, 1995).

Rarely has the death of a child been conveyed with more candor than in the collected moments that make up Exotica, a potent study of grief that lets the anguished exchanges between characters linger, avoiding direct shots to layer excruciating levels of tension. Egoyan allows his characters to grow gradually from the wretchedness of their situation, rather than the other way around. There are very few happy stories in the world. Good stories always involve adversity and conflict. How human beings deal with adversity can create a mosaic of emotions and themes. The universal theme of death dates back to the very first stories ever told. The key is how these particular, ordinary-seeming people react to and deal with devastating adversity.

The film is full of simple, impressive moments, capturing the precise mood of neon soaking into a rain-slick highway, and a chair on which nobody sits. In his stories, plot and character work together. Rather than sacrificing one to develop the other, Egoyan uses each to the benefit of the film. Characters are defined by their need to intervene in the narrative. When the final credits roll, the audience might feel like the story could only have happened with these particular souls, and they should find that entirely satisfying.

The film opens with Thomas (Don McKellar) enduring an airport search. A guard glowers at him through a one-way mirror. At first, it is not clear what connection he shares with Francis (Bruce Greenwood), a tax auditor obsessed with a particular dancer in the strip club. As the film progresses, we see Thomas picking up dark-skinned, "exotic" men at the ballet while Francis drifts into the Exotica nightclub to watch Christina (Mia Kirshner), perform a "schoolgirl" routine that becomes "exotic" within the environment of the club. Francis pays her an hourly rate to come and "dance" at his table. No touching is allowed in this club, but Francis does not want to touch. The bond between them is more complex than that of a regular dancer and client. When Francis says, "How could anyone hurt you?" to Christina, only in retrospect can we understand all the layers in his words. He tells Thomas:

"You know, when the police came to question me, they told me a lot of things. They told me that my wife was having an affair with my brother. Had been for years. They told me that I thought Lisa wasn’t my daughter. They told me I thought she was Harold’s."

"Why would they say that?"

"Because they thought I could harm her. That I would harm her. And then they found the man that did it and they let me go. And I went home. And then my wife was killed in a car accident a couple of months later. Harold was in the car. He lived."

Francis says, "What do you think it would have taken for a father to kill someone?"[8]

When words are drained of their expressive qualities, they become walls, better left ignored. Egoyan wants to decenter his audience. He makes the most familiar agents of communication (including movies) seem foreign. He achieves this by fragmenting the narrative and shifting the texture between video and film. The narrative is not anchored in one particular character. Instead, we have many points of views. In Exotica, the story is framed by sequences of people walking through a sun-dappled field. We recognize the club’s DJ and one of the dancers.

Exotica (Alliance/Miramax, 1995).

They are the only people who could claim this scene as their memory. But the scene’s placement in the film always suggests that it belongs to Francis, the grieving father. The flashback will later reveal that these people are looking for his murdered daughter. It makes thematic, if not dramatic, sense to unfold this scene sequentially as they plunge toward the source of his pain.

The DJ introduces Christina by saying, "What is it that gives a schoolgirl her special innocence?" She embodies Francis' lost daughter, yet in the nightclub setting, his pain, projected onto Christina, has fetishized it out of context. She has become objectified by the watchers, including Zoe the club owner, and those who watch the film.

Zoe’s relationship with Christina mingles the sexual and maternal. Zoe inherited the club from her mother. As a way of coping with the weight of her mother's influence, she has her own child. Thomas is also distraught over his father's death and smuggles eggs under his shirt like an expectant mother. In memory, ordinary experiences can seem exotic.

Jacinto Lageira’s essay, "The Recollection of Scattered Parts," discusses the balance between public and private images in Egoyan’s films. Our memories of words, places, and actions rarely match the images recorded on film or video. We become aware of the gaps between our recollections and those stored on the machine. But not only does "technical memorization" compete with our personal memories, it actually becomes a new part of them. When we watch a film or a home movie, our memories add a second or third layer, superimposed and inserted into the sequences which seem to belong neither to the image or the initial experience. The recorded images bear a close resemblance to memories because they emerge in fragments and are capable of inducing new memories.[9]

According to Lageira, the characters in Egoyan’s films are hunting for memories fixed in images — avid for mechanically recorded eras, voices, gazes, and bodies. They speak little about their own memories, as though to repress them. Vision takes over for individual or group memories and sometimes eclipses words.

The "projection of memory" seems to replace real memory. Egoyan’s films unfold in this way, referring one image to another, reconstructing past events like a jigsaw puzzle. Each piece is already complete in itself. When related to the others, it legitimizes the overall image that takes shape.

While a videotape records images objectively (outside the film/story), the true memory belongs only to a human being:

"Being a singular moment of human experience, whether secret or shared, memory is the final rampart against the depersonalization carried out by machines and the media. But it is the most fragile as well, for the terrible effect involved — collecting diverse references to places, persons, and situations, in the hope of fabricating a memory — often veers dangerously toward the absurd: it is not certain that a whole can be attained, since even this whole will then become another isolated part."[10]

Watching an Egoyan film, we combine two diverging viewpoints: the public and private. The memories captured on videocassettes allow the characters to read their own memories in a different light: sharpening the past and reinterpreting the present along with the spectators of the film. The only coherent point of view belongs to the film, not the characters. This ties into the Egoyan theme of media restructuring our environment — not only what we see, but what we feel and do.

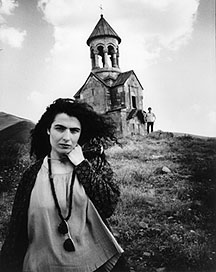

In Calendar, the viewers are voyeurs of their own spectacle. The images of self and the Other complete each other while remaining separate. Egoyan and his wife play a couple on a trip to Armenia. He takes painterly photographs of ancient churches for a calendar. Their guide rambles on in a language only the wife can understand. Since the dialogue lacks subtitles, we have to depend, like the husband, on her for translations. This section is viewed from shaky, hand-held videos and still camera shots taken by the husband. We hear snippets of conversation as the petulant husband grows frustrated with the rapport his wife shares with the charming guide. The guide can’t fathom why the photographer will study the churches in his camera but not step inside them. The wife translates.

"Don’t you feel the need to come closer? Actually touch and feel…"

"Touch and feel the churches?"

"…realize how it’s made, constructed?"

"Hasn’t occurred to me."

"Hasn’t occurred to you?"

"He’d like me to caress them or something?"

"You know what he means."

"No. I don’t, really."[11]

Of course, the photographer does not notice — nor do filmgoers find out — until the husband returns to Canada and studies the videotape he made in Armenia. The next segment is marked by the twelve stages of a calendar. The finished calendar is tacked above a telephone in his barren apartment.

Calendar (Ego/Zeitgeist, 1993).

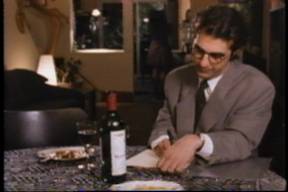

We see a series of scenes of the husband sitting in the next room with assorted young women, as carefully selected as his calendar shots. He pours wine and makes banal small talk until each woman slips away to use the phone. Each woman murmurs a foreign language to the person on the other end of the line. Meanwhile, the husband whips out his notepad and jots impressions in it. His thoughts take the shape of a letter to his wife, clinically analyzing their separation.

Calendar (Ego/Zeitgeist, 1993).

The purpose of the husband's meetings with the women is never explained. These moments resemble auditions, always fizzling when the women sneak off to chat with someone else in a foreign language. Murky sound from one time frame overlaps the other. Video footage speeds in fast-forward or reverse, letting us know that the husband is watching the footage (at one point, he masturbates to the image of his wife). As the film cuts between 8mm video and sleek 35mm footage, the truth emerges from the messages his wife leaves on his answering machine.

Calendar (Ego/Zeitgeist, 1993).

He tries to respond to her by letter, but he does not know how to express himself with words, and his attempts lie in a crumpled pile. He watches his marriage collapse from the safe distance of the camera lens.

All that’s meant to protect us is bound to fall apart. Bound to become contrived, useless and absurd. All that’s meant to protect is bound to isolate. And all that’s meant to isolate is bound to hurt.[12]

The ritualized acts and reenactments play in an obsessive loop, reproducing the husband’s heartache. Jonathan Rosenbaum says:

"The process by which ethnic sites become calendar illustrations — and ethnicity and history become a commodity — entails a chain of communication that passes from nationalist to diasporan to assimilationist, bringing the first two closer together and moving the second two further apart, a chain all of us are involved in nowadays on multiple levels, in relation to both our own families and ethnic roots and those of others." [13]

Video reveals the selective process of memory. To get the most out of his memories, the photographer needs obsessive organization. He sits alone at the table, engulfed in the images and sounds of his imagination, which the film offers us: his wife’s face in the Armenian landscapes, and the man who guided them but could not speak English.

Calendar (Ego/Zeitgeist, 1993).

Egoyan's character resembles a tourist who is more interested in taking pictures than absorbing their history. His remoteness, however, comes from feeling like an outsider in a country that he had always considered to be his homeland. Egoyan comments on the photographer's inability to see what is right in front of him. We see only what he sees. In a way, we are just as blind. Egoyan connects on-screen and offscreen voices, English and other languages, urban and rural settings, their doppelgängers in video and still photography, creating intricate patterns out of his usual themes of family discord. His elliptical films loop through time and double back to take another glimpse at his characters' lives.

Lageira describes Calendar as a multi-faceted mirror where the Other multiplies and shatters into fragments. The first obstacle is language. The unseen narrator needs an interpreter to translate the guide’s words. The narrator (whose face is absent from the screen in the Armenian scenes) is exotic to the film, but the people he films appear exotic to him.

The guide functions as a reference point for the girlfriend’s memory. In him, she rediscovers a part of her identity. Lageira describes him as the Other as rival:

"Situated between the lives of the cameraman and his companion, the person of the guide crystallizes the same and the other, stranger and friend, a moment of identification and of rejection."[14]

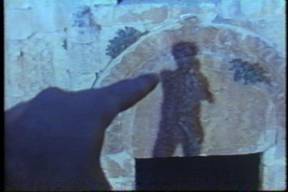

In one elegant shot, the guide ducks behind the narrator while he films his shadow on the wall. The two shadows blend so we cannot tell them apart from each other. The film freezes, as if to explain that the Other is always our own double.

Calendar (Ego/Zeitgeist, 1993).

For the characters who have actually lived the scenes and images that they watch, the machine never physically or materially replaces the bodies and memories; wheras for those who literally invent their memories, plucking them from the imaginary and not the real, the electronic memory is what creates the memory of the viewer, replacing his own power of recall. The first have to reassemble the pieces of an already existing puzzle in order to create their memory, where the second group have to fabricate the pieces they are putting together. But both are caught in the same trap. Memory must become image.[15]

The camera’s memory cannot dream or imagine. It simply presents what has been filmed. The spectators are the ones who interpret it as a memory. Egoyan’s existential dilemma says there is no memory without an image to watermark it. Without images, there are no memories. By continuously imagining or projectioning their memories, his characters search for meaning in their lives, a structure beyond the chaos. After the characters have died, their memories will continue living in the machines, granting them a symbolic immortality.

In Video Letters, a discussion between Egoyan and Paul Virilio, which took place by videocassette in 1993, the director says:

"What I choose to do by presenting video images within the film is to make the viewer very aware that the image is a construct. The image is a mechanical process of projection, and the viewers are made aware of that process by seeing the video image within the film image."[16]

Another reoccurring theme in Egoyan’s work is the family romance. The intimacies of family life are projected as public domain through technology. The Sweet Hereafter, winner of the Grand Prix at the Cannes International film festival, reflects back to Exotica, where the grieving father survives two tragedies: his daughter’s murder and his wife’s death in a car crash. Isolated from his community, he tries to build a new one by recreating the past.

In The Sweet Hereafter, based on Russell Banks’ novel, Egoyan charts the emotional course of several characters who share deep guilt in their pasts. The residents of Sam Dent each narrate their different versions of events in intriguing Rashomon style. A series of interconnected vignettes revolve around a tragic school bus accident in a small town. The film switches between the time that Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm), a big-city lawyer, arrives in town to "help" the families receive compensation, to the days leading up to the moment when the school bus swerves off the road, crashes through a guard rail and plunges into a frozen lake with the children aboard.

In the opening sequence, Mitchell sits alone in a car wash, surrounded by suds and the soothing whoosh of water. The ring of his cell-phone invades the silence. It’s his daughter, Zoe (Caethan Banks). Intercutting between their conversation, Egoyan reveals how the lonely father and daughter live in separate realities. Mitchell speaks from the insulated comfort of his luxury car. Zoe is calling from a pay phone on a barren street. He tries to reason with his drug-addicted daughter, but feels at fault when she will not listen to him. He faces an ongoing tragedy every time he answers his cell phone ("This is my daughter ringing, or it could be the police telling me that she’s dead").

After their terse conversation cuts off, the car wash breaks down. Mitchell is forced to climb out of his car. On a symbolic level, he is also stuck: unable to move past his guilt.[17] Wrapped in his own frustration, he has become emotionally frozen. He had once saved his daughter’s life when she was a baby, but now she has turned away from him. His feelings are unresolved. He wavers between wanting to reach out to his daughter and deciding to cut her off. "I don't know who I'm talking to right now," he says. When he finally gets out, he wanders through the deserted service station, looking for someone to blame. Mitchell, much like the film’s spectators, becomes a voyeur, peering at the mangled bus through the shop windows. He is not simply after a quick buck (he receives 1/3 of the proceeds from any favorable settlement), but believes that his own tragedy forges an emotional link between him and the townspeople. His probing into the town’s darker secrets eventually does more damage than the accident itself. Like the French woman in Hiroshima, Mon Amour, they must forget their traumatic past in order to go on living. In the tradition of the nouveau roman, Egoyan favors meditations on memory, subjectivity and the nature of human relationships.

Katherine Monk describes the bus as the main repository of guilt in the community, the centerpiece in Mitchell’s class-action suit on the families. "Let me direct your rage," he tells one prospective client. He wants to alleviate the families’ pain, projecting the negative energy at some nameless entity, but he twists the facts to ease his own remorse. The Sweet Hereafter echoes the structure of an epic Western. Mitchell rides into the rural community and tries to become their hero.

"There is no such thing as an accident; somewhere, someone decided to cut a corner," he says. Blaming the town, the bus company, and the school board, Mitchell presents himself as the only one who knows what is best for the families. Mitchell is no ambulance chaser. When he says, "I will sue for negligence until they bleed," he is clouded by his own rage. There is no clear culprit to sue for the bus accident. The grief-numbed parents join him in the hope that money will soothe the pain, but their greed for compensation fractures the community.

The film moves from sprawling, snow-flecked exteriors to dimly lit interior spaces as it reveals the hidden motivations and connections between characters. Through Mitchell’s eyes, Egoyan introduces a myriad of small-town lives. We meet Dolores, (Gabrielle Rose) the middle-aged bus driver, who was behind the wheel during the accident. She adored her precious cargo, the students she saw as her "kids", and can’t bear their loss. Dolores tries to escape her pain through denial but remains racked with guilt. She speaks of the children in the present tense, but then breaks off and says of one boy, "He would have made a wonderful man."

The sole survivor of the accident is a teenager, Nicole (Sarah Polley), the town’s golden girl, a popular student and victim of her father's sexual longing. Now she is confined to a wheelchair. Her testimony is pivotal. Under pressure from her doting father she decides to give evidence. If called to do so, she will tell all the truth — the implication made clear in a flashback to their candlelit tryst. But what is her tie to the truth? Even in appearance, Nicole is ambivalent. Is she a girl or a woman? Nicole is caught in a Lolita-style affair with her own father. Egoyan links her to the "abandoned crippled child" in Browning’s "Pied Piper of Hamelin" — the lone child left behind from the land where "everything was strange and new."

"When, lo, as they reached the mountain-side,

A wondrous portal opened wide,

As if a cavern was suddenly hollowed;

And the Piper advanced and the children followed,

And when all were in to the very last,

The door in the mountainside shut fast …" [18]

Egoyan weaves this motif throughout the film to reinforce ideas of responsibility and guilt. One of the children that Nicole baby-sits asks a crucial question: "Well, if he knew magic, if he could get the kids into the mountain, why couldn't he use his magic pipe to make the people pay him for getting rid of the rats?" Nicole explains that the Piper wanted to punish the town because he was very angry. A key scene between Mitchell and Nicole’s father shows that the theme extends beyond the bus tragedy:

"I'm telling you this because … we've all lost our children, Mr. Ansel. They're dead to us. They kill each other in the streets. They wander comatose in shopping malls. They're paralyzed in front of televisions. Something terrible has happened that's taken our children away. It's too late. They're gone."[19]

Both Mitchell and Mr. Ansel have lost their daughters. The guilt-ridden Mr. Ansel tries to regain Nicole’s affection by building a princess castle for her after she returns home from the hospital, but she rejects him. ``You'd make a great poker played, kid,'' the lawyer says. She not only feels guilty about surviving, she mourns the loss of her innocence. When Nicole demands a lock on her door, she has finally gained control. At the end of the film, Nicole’s response to the lawsuit has not only destroyed the community, but paved the way for a new one.

The film hovers around the themes of public and private loss, and the human need to find meaning in an inexplicable tragedy. We meet a gentle "hippie" couple, Wanda (Arsinee Khanjian) and Hartley Otto (Earl Pastko), whose loss of their adopted Native American son has filled them with the need for revenge; a caring mother of a learning disabled boy; and the widower (Bruce Greenwood) who follows his beloved son and daughter to school in his pickup truck. The widower is having an affair with the mother of the learning disabled boy (she is unhappily married to a loathsome husband). He doesn't want to talk about the accident. To him, the town should take care of its own pain without the interference of outsiders.

Perhaps these "good, upstanding neighbors" have played some part in the accident. In one of the most eloquent scenes, we see the bus hesitate on the ice before sinking into the cold black water. In the distance, the widower watches in horror, unable to rescue his own children. Why should they be allowed to live while 14 innocent children are dead?

This is the question that binds the film. The opening credits play over the simplest and most primal of scenes. Naked and dozing under white sheets, a mother and father share their bed with a baby. It's a fantasy of togetherness that contrasts with the darker scenarios of family devastation that gradually unfold in the film.

When this idyllic image appears for the second time, it frames the introduction to the school bus accident. The scene is Mitchell’s recollection of the morning when he saved his daughter’s life. During a long plane ride, Mitchell reveals the wrenching, story in flashback. As a toddler, Mitchell’s daughter was poisoned by spider bites. After phoning the doctor, he learned that he might need to perform an emergency tracheotomy. "I was prepared to go all the way," Mitchell says.

Egoyan complements these words with a devastating visual. We see a wide-eyed little girl lying against a car seat as her father sings a lullaby. A knife glistens inches away from her face. In this way, Mitchell' experience merges with the townspeople’s living nightmare. By evoking his private memories with present events, the film combines two timelines. To heal, the characters, much like the lovers in Hiroshima, Mon Amour, must forget their traumatic experiences as separate events and remember them in context. The townspeople and the lawyer are ripped apart by their memories. They both need to remember and to forget. Katherine Monk writes:

"In a Biblical context, Abraham’s gesture was enough to appease God and prove his loyalty to the one and only Creator. In The Sweet Hereafter, the imagery is secularized and internalized into one system. Mitchell’s readiness to cut his child’s throat is a testament to his love for his child."[20]

Now Zoe has grown and the dynamic has changed. When she tells her father that she has tested positive for HIV, he feels that he has lost her again. Her life is in danger and he is unable to protect his little girl. Monk says:

"He was ready for the knife, but is he ready to be heartbroken by her addiction all over again? The answer is always the same: Yes, because he loves her. And that love is both his burden and his salvation. A step in the wrong direction and guilt will follow, hounding you until the end — eating you alive — until one dies, or finds forgiveness in the eyes of God (Abraham), one’s peers (Dolores), or oneself (Mitchell, Nicole)."[21]

When Nicole experiences incest with her father, she realizes that she is being abused. She was robbed of her childhood by a parent who stepped beyond the bounds of trust. Seeing her father in a state of denial, then watching him negotiate her broken body for a reward, she becomes outraged. Egoyan shot the incest scene from Nicole’s point of view as it happened. Their quasi-romantic scene in the candlelit barn is an attempt to show how she might have described that particular moment.

The Sweet Hereafter (Alliance/New Line, 1997).

In some ways, it's not dissimilar from the way the bus accident itself was shot — from the widower’s point of view, as he would have experienced that moment. As opposed to the typical Hollywood-style action sequence, which might cover that accident from as many angles as possible, Egoyan shows the effect of what it would feel like inside that bus. Egoyan takes time to show us the school bus winding through the hills as it has done many times before. Filming the crash without sound, Egoyan creates a surreal and unforgettable image — a slash of yellow careening off a mountain road and drifting onto the ice.

The Sweet Hereafter (Alliance/New Line, 1997).

In an interview published in Cineaste magazine, Egoyan says:

"I find cinema is a great medium to explore ideas of loss, because of the nature of how an image affects us and how we relate to our own memory and especially how memory has changed with the advent of motion pictures with their ability to record experience. Our relationship as filmmakers to those issues has changed radically over the past fifteen or twenty years. And people in our society have the instruments available to document and archive their own history. In my earlier films, I was exploring this in quite a literal way. But the ways in which our ability-and our need-to remember have been transmogrified comes very much into the spirit of this film as well."[22]

In his work, we no longer identify with the protagonist alone, but also with aspects of the image, the unseen presence making choices behind the camera. The images on the screen have already been organized. This redoubling includes the spectator in the image, calling attention to the silent viewers on the other side of the screen.

"There's nothing casual about accessing memory or the way experience is evoked," says Egoyan. "There's something very self-conscious, quite determined about it — the way people manipulate or use their own experience to get things they want from other people. Or the way some people want to relate to their loss in a very immediate and private way and are threatened by having that intruded on them.[23]"

Once again, Egoyan makes use of videotape as an inherent part of the narrative and a sign of detachment (Mitchell films the bus interior, searching for evidence, and the little boy, Bear, is viewed in another scene on a family home movie). When video and film images mingle, so do the frames of reference. It’s difficult to determine from where (and whose perspective) the image stems. Often he uses a high-angle medium shot that suggests public surveillance cameras. His scenes are blocked with the stiffness of TV sitcoms, enforcing the sense of voyeurism.

The video image may trigger gaps in time and logic, forcing the viewer into becoming part of the narrative process, into what Monk calls "the metaphysical fabric" beyond the frame. Instead of looking at it passively, Egoyan wants viewers to gain control of these imagistic representations of life through a degree of personal involvement. He demands that we question his films and their meaning. We scrutinize the morality of his characters and the motivations of the filmmaker himself.

Although a photograph can only represent the past, cinema’s illusion of movement attempts to put the missing pieces of time back into an image. The cinema of Alain Resnais and Atom Egoyan share a thematic approach to time and the creative aspect of memory. As the audience of their films, we are active participants in their message. In a sense, we are also their film’s subject.