A reading of Elizabethtown

Ruining plans; reconciling aesthetics and life

|

|

by Daniel Garrett |

Elizabethtown

A screenplay by Cameron Crowe

Faber and Faber Limited

London, New York, 2005

ISBN 0-571-22881-x

$13.00

“Every movie has its own world, and its own language, but I’ve always held a special affection for the personal films that a director makes with no one looking over his shoulder, and only his private heart as a guide.”

—Cameron Crowe (Introduction, Elizabethtown)

What is beauty in language and thought? Beauty in language and thought is eloquence, fine feeling, insight, and wit; and it is language suffused with the imagination of the connections among the realities that do exist and imagination of connections that might come to exist. Cameron Crowe wrote the script for the film Elizabethtown, and I like the script more than I liked the completed film: it’s a beautiful screenplay; and it is the words on the page that incline me to think that the film might one day be rediscovered and acclaimed—even acclaimed a classic.

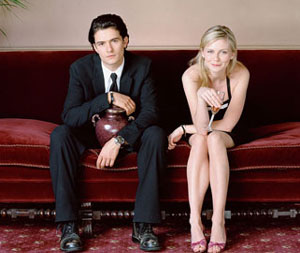

The script of Elizabethtown was made into a film in 2005 by Cameron Crowe, who had directed Jerry Maguire and Almost Famous, two films I liked. I found the film Elizabethtown to be intriguing and entertaining but frustrating: it is a film about a young man, Drew Baylor, whose shoe design is first a much heralded creation and then a business failure; and the same day the young man is fired and his co-worker girlfriend drops him, Drew’s consequent plans for suicide are interrupted when he is told his father has died, and Drew must return by plane to his father’s childhood home, in Elizabethtown, near Louisville in Kentucky, to reclaim the body. Elizabethtown starred Orlando Bloom as Drew, Kirsten Dunst as Drew’s new stewardess friend Claire Colburn, Susan Sarandon as Drew’s mother Hollie, Judy Greer as Drew’s sister Heather, Paul Schneider as Drew’s cousin Jessie Baylor, Loudon Wainwright III as Drew’s Uncle Dale and Gailard Sartain as Charles Dean, a friend of Drew’s father and the funeral manager. The film, which has elements of both comedy and drama, gave amusement, and was intelligent and sensitive in ways that are longed for, but its vision seemed more aesthetic than real. (It was very glossy.) I felt guilty for not liking it more, and yet I regarded it fondly despite my reservations about it: strange.

I had thought that Cameron Crowe’s concern with the film’s aesthetic, its cinematography and production design, had sabotaged the film. The aesthetic—the concern for form, for thoughtful pleasure, for the way things are seen and experienced—can have a deadly effect on energy and warmth; and yet it is possible that the film, which seems to be about failure and success, family, love, and identifying the genuine interests and resources of the self, is actually also about the aesthetic; and that the aesthetic realm in the film is represented by the lead character’s shoe design, and by Claire Colburn’s sense of the roles she and Drew play in other people’s lives, Jessie’s rock band, Hollie’s tap dance, and by the gift of an elaborate map with music that Claire gives to Drew near the film’s end. The experiences that Drew begins to have when he follows that map involve his spirit—without piety, they are spiritual encounters—but they are also aesthetic. It is possible that all the moments of reconciliation in the film create a harmony that can be considered aesthetic. It is arguable that the film is partly about how to reconcile the aesthetic with the real, something I did not consider until I read Cameron Crowe’s screenplay, which is, simply, one of the most fine, imaginative, and thoughtful (one of the most beautiful) pieces of writing I have read.

How is the aesthetic reconciled with the real? What is real? Nature—land, water, sky, air, are real. The human body and human consciousness and human society are real. However, our relationship to nature and to each other can be subject to interpretations that are more illusion than reality: fantasy, hope, nightmare, prejudice. In the film Elizabethtown, Drew had an idea for a shoe, he designed it, a lot of money was invested in it, and it seems after the shoe was manufactured and began to be distributed something was wrong with it—we aren’t told what. His design did not suit the feet in the way he planned: someone says people may return to walking barefoot because of it.

The film, like the screenplay, begins with Drew’s elucidation of the difference between a failure and a fiasco, with a fiasco being “a disaster of mythic proportions” (page 4). Drew’s failing is costing his company—or rather, the company that employed him—about a billion dollars. A film that takes work, and the modern office environment, as a subject is unusual: the ambition, the creativity, the camaraderie, and the short-lived loyalties are sometimes referred to, but are not often dramatized in most films. In Crowe’s screenplay and film, the work place is what we are shown. Drew arrives at headquarters to meet with his boss and the company owner, Phil (actor Alec Baldwin), who gave Drew his head, his ability to pursue his own talent, and will give him his head again, almost on a platter, with his dismissal and a public humiliation. “They tell me we’re about to lose 972 million dollars. I’m ill-equipped in the philosophies of failure,” says Phil, who takes Drew on a tour of the great facility (9). Phil says, “I cry a lot lately” (10). In the film these words coming from Alec Baldwin, so perceptibly assured a man, a man with a gleaming surface, sharp, slightly ironic, these words from Baldwin’s lips are unexpectedly poignant and funny for their poignancy. Phil tells Drew he wants him to talk with a reporter from a business magazine, and wants Drew to convey that the company had invested in Drew’s brilliance and “I think you should stand up for your incredible work” (11). It is one of the few times when the word incredible is used appropriately in a film. Phil wants Drew to take full public responsibility for the fiasco. When Drew meets with the reporter, and does begin to take responsibility, Crowe’s notes say, “The smell of corporate violence is in the air. The pack needs to devour a wounded animal” (13). What is required is a scapegoat: an obvious cause, an obvious victim—and closure.

Drew is escorted from headquarters. He goes home, and rigs a suicide machine, using an exercise cycle and a long knife, a machine that convinces us of his creativity, and the call about his father’s death interrupts him. Drew takes a flight to Kentucky, on which he meets the stewardess Claire, a young woman who might be dismissed as merely quirky, if her conversations and acts did not reveal that her quirks are the results of very critical and perceptive thoughts and values: she has social and spiritual senses. She talks about how people are alike—“I’m a student of names” she says (29), and talks about how Phils or Ellens are alike. (Ellen, Drew’s co-worker, played in the film by Jessica Biel, seems to have become involved with Drew not for himself but as part of her participation in the corporate atmosphere.) Names, for Claire, are a kind of trope for conformity, for predictable behavior. Claire also has an instinct for why Drew is traveling with a blue suit, for a funeral, without being told: something that indicates imagination and empathy. Claire tries to teach Drew how to say Louisville: Loua—vull. She gives him travel advice for how to get to Elizabethtown—rental cars, roads, and she gives her phone numbers. She is very responsive.

Drew arrives in town, late, and everyone seems to be expecting him. He meets Jessie Baylor, his cousin, also a young man, who tells him, “This loss will be met by a hurricane of love, and you are staying with me!” (37). They could be brothers (Jessie calls Drew brother at one point, an indication that it’s something he wants or needs; and Crowe’s screenplay notes say that Jessie is glad to have someone his own age around). The two young men might have been friends, if they weren’t family. One thing that they have in common is failure. (Is it possible the young now have a harder time establishing themselves than their elders? Is that because the economy is more complicated? Or because expectations are more idiosyncratic?) Jessie doesn’t have the respect he might have had from the other men in his family, nor even from his own young and screaming, trouble-making son. Jessie’s band, Ruckus, failed years before, and Jessie has quit his job in order to think. “I’ve taken the year off for hard thought…tough thinking. Something big has happened…or is happen-ning, and I want to be the guy who puts his finger on it. Creatively,” Jessie says (51). Leaving something concrete (work, money) for something abstract (thinking) is not very American, and is frowned on: the judgment is hardly ever that you’re doing what you say, but rather that you simply want to avoid something, or that you’re indulging some hedonistic pleasure. Another thing that Drew and Jessie have in common is that they are both—to one extent or another—artists: one sees a blank page and fills it, with a design, and the other hears silence and fills it, with music; they create something new. But their artistry seems to have been rejected by the world. What do you do when that happens? Kill yourself, as Drew contemplates? Withdraw from the world, as Jessie has done? Artists are known for their independence, but it is almost always—and possibly inevitably—an incomplete or limited independence. What does it mean to design a shoe that no one else makes or wears? What does it mean to make music that no one else hears or likes? The audience completes the artist; doesn’t it? Or is it the art that completes the artist?

Jessie, like Claire, extends himself: he instructs Drew in how to receive mourners. When Drew arrived in town, it was obvious that he was not used to death or interacting with an extended family: Drew offered condolences to others, though as the Mitchell’s closest relative in town, the condolences are to be offered to Drew. (“They’re gonna say—‘Sorry for your loss.’ And you’re gonna say ‘Thank you for your thoughts,’” says Jessie, on page 44.) Jessie, like Claire, can be very understanding: he knows why Drew’s mother has not immediately come (“I don’t blame her. Around here, their favorite thing in the world is to get offended by something small, and hold on to it for fifty years); and he recognizes the distance Drew must have had with his father (When Drew claims to have known his father very well, Jessie ignores Drew’s rambling affirmation and says, “Yeah, I don’t know my father very well either”) (50).

Amid a family gathering, Jessie’s son, Samson, is wild—dropping a cooked ham on the floor, stopping up a water dispenser, driving Drew’s rented car. “You’ve got to take control of your kid! That boy is looking for rules from you!” Dale says to Jessie (48). What kind of father does a man have, what kind of son will this make him, and what kind of father will he himself be? After a long conversation with Claire, in which Drew mentions the boy, Claire gives Drew a tape for Samson that captures Samson’s attention—on the tape, a tough man takes him through the blowing up and rebuilding of a house, and so it is a tape that acknowledges and gratifies the child’s desire for destruction and creativity and respect for formidable authority. The tape is an aesthetic object with a practical use and it brings Samson closer to what Jessie and Jessie’s family want Samson to be.

When Jessie announces his rock band is reforming to participate in Drew’s father’s memorial celebration, something that might be a renewal of Jessie’s creativity, Jessie gets no response from his family: Crowe notes, “In ways large and small he has ceased to command respect…or even their attention” (90). That’s brutal. The performance is a point of pride for Jessie. Unfortunately, there is an accident involving one of the props for Jessie’s band at the memorial, a fire is started, and people must be evacuated. (Stewardess Claire helps; whereas, Chuck is angry, as he had planned to follow with his wedding celebration in the now ruined hall.) The fire is another disaster for Jessie, while it proves Claire’s mettle, and gives the family a shared experience—terror, absurdity—and the film’s viewing audience laughs (I laughed as a viewer, and winced as a reader, as I wanted Jessie to have not only the pleasure of Drew’s company, and that of his bandmates, but also public success).

The film, true to the screenplay, allows several of its characters to have a significant experience. Drew’s mother Hollie grows—from being estranged from her husband’s family to accepting them; from being adrift in her own life to being its central focus and force. Early in the film Hollie says the two sides of the family never integrated well. That is because, before meeting her, her husband had a fiancée and plans to return to his hometown, and after meeting her he moved with her first to California then to Oregon (she and her future husband ruined each other’s plans by falling in love). Her husband Mitchell did write and visit Elizabethtown, but without his wife and children and he died on one of his visits. “I was still waiting for everything to start and now it’s over,” Hollie says about her life early in the film, when walking Drew to his plane for his trip to Kentucky (22). She wants her son, whom she sees as the most successful person in the family, to represent her family to her husband’s family (Drew has said nothing about the fault that has been found with his new shoe). Hollie’s husband Mitchell was a beloved figure for the town he left, and someone seen as a happy and fun guy (his son, Drew, saw him as more serious: when the son arrives and sees the look on his father’s face as he lies in his casket, Drew is first surprised by the whimsicality, something the embalmer, a friend of his father, saw and preserved. Drew’s sister will say, later, without trying to be mean, that their father could be fun—but Drew was too busy with work to share in that). The film is about Drew’s evolution—in joy, in values; and it is also about his mother’s liberation. Hollie has been one kind of woman—she describes herself as she thinks she’s seen, as a humorless liberal Catholic—and her husband’s death reminded her of time’s passage; and she’s motivated to quickly learn things she never learned: to fix a bathroom, to cook, to tap dance, to tell jokes. (Her enthusiasm inspires her daughter’s dread and hysteria.) The Oregon family, Hollie and her children, want the father cremated; and the Kentucky family expects Mitchell to be buried in the town’s cemetery. When Hollie decides to attend the funeral and arrives in her husband’s hometown—after learning that a nemesis, Bill Banyon, who had involved her husband in a questionable business deal, will be at the funeral—she talks to her husband’s family at his memorial, acknowledging the family’s estrangement and also the grief they now share. Hollie’s performance before her husband’s family—her comfort onstage, her honesty, her humor, her dance—show her growth, her acceptance of them and her willingness to be vulnerable. (She even mentions being almost ready to forgive Bill Banyon.) “It takes time to extract joy from life,” she tells them (117), as she combines her genuine emotion with a performance: a moment of different kinds of reconciliation. Hollie’s testament occurs before the accident involving fire that causes the crowd to flee the celebration. There is then a funeral with Mitchell’s blue suit on an empty casket and the urn of Mitchell’s ashes nearby; and all are assembled, and after their shared grief and reminiscences there is a sense of irony about it all.

The burial in a family plot and the ashes in an urn have satisfied, to one extent or another, both branches of the family. Drew’s arrival as the representative of his mother and family had introduced a conflict regarding the father’s burial—brown suit or blue, burial or cremation? Values (and traditions) were embodied in that conflict. When Drew first met the gathered Elizabethtown family and he looked at them, seeing—as Crowe wrote—“pieces of recognizable noses and eyes, elements of his father’s looks…all different spins on the same gene pool” (41), Drew began to become familiar with them. Mitchell’s family referred insistently to Drew, his mother, and his sister as living in California, rather than the Oregon where they do reside, an echo of an old complaint. (The family never got over the first move.) They began to take Drew more seriously when he asserted his mother’s wish that his father be cremated and also showed an interest in Jessie and in Samson’s upbringing. About his father, Drew told them, “You all have different versions of him that you all love a lot. This is ours, my family’s record of the last thing he said on the subject. That’s the way it’s going to be, guys. Sprinkled at sea. And that’s the decision from California. (Beat.) Shit. (Beat) Oregon” (91). Mitchell’s family laughs at Drew’s momentary appropriation of their sense of his origin. Then Drew walks out of the room to give Jessie a video tape he thinks will help Samson (the adults welcome the subsequent and rare silence in the house). Crowe notes about Drew, “The kid is starting to truly impress them” (91). Drew sees a photograph of his father at the same time an aunt has lit a stove to cook; and he, actually, too late, decides—hysterically, funnily—to stop the cremation.

At the memorial celebration, before the funeral, Bill Banyon will cry, and others will talk of the dead Mitchell’s care, concern, support, and his personal habits (“those tiny black shoes, smoking that tiny black pipe,” 112). Hearing Drew—his glibness, his appreciation for the commemorative actions of others—his aunts say that his father’s death has not really hit Drew yet (he does not cry until he takes the road trip Claire suggested, during which he distributes his father’s ashes).

One of the most important relationships in the film is, of course, between Drew and Claire, played by Orlando Bloom and Kirsten Dunst; and that is partly because of how she allows him to see and respond a little differently to his own experiences. After Drew arrives in town, meets his father’s family and moves into Jessie’s house—and then moves out of Jessie’s too-noisy house and into a hotel, Drew and Claire have a long, digressive, phone conversation—about Drew’s father’s death, his father’s family, his lack of travel experience, Jessie’s wild son, religion, vocal accents, perspective. The scene works in the film better than it reads in the book. It’s a charming, funny talk; and they end up agreeing to meet on a highway to watch the sunrise. Claire is confident and self-mocking, and she pays attention: which means a certain flexibility, a certain responsiveness. Helpful Claire helps Drew pick out an urn for his father’s ashes. Drew doesn’t think he can become involved with Claire though: he doesn’t realize that they are already involved.

One of Drew’s standards is the declared love of a new acquaintance, Chuck, for his fiancée, Cindy. (Drew thinks someone should love Claire as much as Chuck loves Cindy.) Drew met Chuck in the hotel he is staying in, the hotel in which Chuck is marrying Cindy. Chuck is very direct, friendly, and happy; and upon learning of Drew’s father’s death, Chuck cries and befriends Drew. “Death and life and death and life. Right next door to each other…Once you start seeing the Big Fucking Picture, you cannot go backwards,” Chuck tells Drew (70). Chuck is willing to postpone his wedding celebration so Drew can have his father Mitchell’s memorial celebration there, in the hotel ballroom.

Drew explains his reluctance to start a relationship to Claire. “I can’t make an attachment here because I’m just going to disappoint you in a very profound way,” he says (85), before admitting, “You’re kind of great, Claire. You do know that? Sort of amazing even” (86). She says, “Come on. I don’t need an ice-cream cone,” which she defines as “a little something to make you happy…Something sweet that melts in five minutes” (86). Then, she tells him her theory that she and he are substitute people, taking the place of ideals in other people’s lives, until those ideal people appear, something she says works for her as she likes being alone. They almost kiss, but reassure themselves it’s better they do not. After his father is cremated, Claire, slightly tipsy, admits that she likes Drew. He, following her admittance that she has been stood up by her boyfriend, says she should be important to someone and kisses her. Drew says, “He’s lucky I’m not the right person for you” (102). She—amusingly, poignantly—says, “I know why it’s not you, but just tell me so I know from your perspective” (102). They do make love: have sex. The next morning, they talk about their relationship and his work (and his self-pity), and she rejects his assessment of his failure, saying that his company took a gamble on him “because it’s their business to gamble…and it’s also their business to use you as a scapegoat. Come on. You’re an artist, man. Your job is to break through barriers, not accept blame and bow and say, ‘Thank you, I’ll go away now’” (108).

Claire, at the memorial celebration, brings the map with music to Drew for his cross-country trip: and on his trip, Drew sees a dinosaur park built by a Christian sculptor, and the Lorraine motel where Martin King was killed, and Oklahoma City’s post-bombing Survivor Tree, and the world’s second largest farmer’s market. Cameron Crowe acknowledges only obliquely the political times, despite the excursions to Memphis and Oklahoma City (and despite what happened when Drew, in Oregon, picked up his luggage at an airport checkpoint before for his trip to Kentucky: Drew’s last minute plane reservation, and having a small pair of scissors, and one-time visit to Germany, led airport guards to consider the possibility of his terrorist potential, part of the paranoia that followed the September 11, 2001 destruction of the World Trade Center—until Drew explained to the guards his father’s sudden death). When Drew explores notable American sites in Memphis and Oklahoma City, the reason why some of them are important—the political conflicts that created social meaning—are not fully explored. Do we need Crowe to be more explicit? He need be explicit only if that is an innate part of his subject or theme (such as his depiction of office politics, which is murder with manners). On his trip, Drew realizes he worked hard to be a success to impress his father, not his boss, Phil. Drew also begins to see the shoe he designed on people’s feet, and the fact that people have made crude adaptations of the shoe, and are pleased with it—so it is not the anticipated fiasco, a fact confirmed by a brief phone conversation with a design collaborator. The shoe has been adapted to the needs—and wants—of the world; the aesthetic and real have been reconciled.

Drew’s journey is marked by rituals of spirit, and the popular music he listens to become contemporary spirituals. (“For minutes on end, Orlando drives and cries and laughs, and talks to Mitch, his father in the urn, and it’s magical,” writes Cameron Crowe in an excerpt from his filmmaking diary, page 169, published with the screenplay and photos from the shoot. Orlando Bloom’s handsome face and sensitive temperament, which can make him seem ethereal, become an idealized embodiment of a universal journey to greater awareness and deeper feeling, a sign of the reconciliation between the ordinary and the transcendent.) To top it all off, Drew finds Claire at the farmer’s market he visits, per her mapped instructions, and confesses his love: “…you’ve ruined all my plans, and I want to do the same for you” (139).