The Ebb and Flow of the Erotic Thriller Genre in the US

Mickey Rourke’s Ventures into the Land of Softcore Cinema

By Jens Nepper |

“I don’t feel much of anything. I’m just weak. Women are my addiction.” Ed Altman (Mickey Rourke) in Exit in Red (1996)

Introduction:

Mickey Rourke may not be the first name that comes to mind when thinking of softcore cinema, but a closer study of his appearances in erotic softcore films can be tied in with a rather interesting historical development of the aforementioned genre, its cultural impact and its rise to success within mainstream cinema, as well as its drift away from impressive sales figures at the box office. When viewed chronologically, the erotic movies in which Rourke has appeared are worth looking into in terms of the genre’s highlights and failures, exemplified by, for instance, the major success of the first 9½ Weeks (1986) and the miserable reception that the sequel, Another 9½ Weeks (1997), received by viewers and critics. Professor Linda Ruth Williams sums it up perfectly when stating:

Mickey Rourke’s career plummet too can be traced in his work in softcore sex films, from mainstream success like 9½ Weeks and Angel Heart, to the DTV work of Love in Paris (aka Another 9½ Weeks), Wild Orchid and Exit in Red. Only the last two are erotic thrillers; the 9½ Weeks films are erotic melodramas, whilst Angel Heart is a horror film. All have strong softcore elements running through them which sexualise Rourke (though he is seldom a beefcake equivalent of the female cheese cake), making him a fascinating figure for discussions of contemporary masculinity and performance, shot through with an existential aloofness, and lately a beaten-up quality. (2005: 148)

Some of Rourke's biggest commercial hits and failures are erotic thrillers and softcore films, thus he figures as an important, although often overlooked, key-player within the erotic softcore genre and its relation to not only mainstream cinema, but also the somewhat steady direct-to-video market of softcore releases.

The main objective of this article is to shed light on how Rourke ties in with softcore cinema and how certain patterns within the films he has appeared in have developed and repeated themselves throughout his career, most notably in terms of how he, more often than not, ends up as the fall-guy. Apart from the primary emphasis on Rourke’s ventures into the land of softcore cinema, the intention of the article is also to bring his work within the genre into a larger perspective and raise a few points of discussion regarding the genre in an overall perspective, more specifically its cultural impact, its relation to censorship, film noir, and erotic thriller archetypes such as the femme fatale and the fall-guy.

In terms of genre conventions, the erotic thriller genre is in itself a dynamic genre-hybrid that has often been capable of mutating into new genre-blends and gain new territory. Although it is quite diffuse in the sense that it cannot be viewed and perceived as a closed and fixed system of codes and conventions, it could however be argued that due to these being applied so frequently in films labelled erotic thrillers, a narrative template and framework is somewhat established for this cross-breeding genre. Patterns overlap, however, and the dividing line is never one hundred percent visible. Linda Ruth Williams offers an interesting take on the subject:

I read the erotic thriller as a fluid, often hybrid genre, perhaps at its 'purest' in the most formulaic DTV examples, bleeding into and out of adjacent forms such as classic noir, neo-noir, porn, the woman’s film, serial killer and horror films, and the auteur-led art-film.” (2005: 26)

The ability of genres to attain new meaning and constantly be re-evaluated over time is also discussed by Professor Frank Krutnik, who, in his study on film noir, argues that genres exist across various forms of culture, be it popular or commercial culture, and that “Genres are dynamic in that they accumulate meaning through time – they do not simply reiterate a stock set of themes, settings, character types and plot elements.” (1991: 10)

In a larger perspective, cinematic sex and the representation thereof is subject to a variety of different factors and forces. To quote Professor Tanya Krzywinska: “Cinematic sex, in whatever guise, is squeezed into shape by the exertion of various forces. These can be divided into the following: aesthetic and formal; industrial and market-based; institutional, discursive and socio-cultural-historical.” (2006: 6) This article is not concerned with a detailed account of any of the aforementioned forces as such, but rather serves as an accessible map of certain key issues, such as those outlined by Krzywinska, that are relevant when discussing, analysing and interpreting erotic thrillers and softcore films. The following three softcore films, all starring Rourke, will serve as the primary vehicles of discussion throughout this article: 9½ Weeks (1986), Another 9½ Weeks (1997) and Exit in Red (1996).

1. Mickey Rourke, The Femme Fatale and the Fall-Guy Syndrome:

“In many ways the femme fatale is the erotic thriller, central to a sexual-action-oriented genre focused on spectres of violent, eroticised death.”1.

One of the most enduring figures of the erotic thriller genre, and film noir in general, is the femme fatale, as well as its male parallel; the homme fatale. In terms of cinema, the femme fatale derives, as hinted before, in large part from the noir films of the 1940s and 50s. Frank Krutnik argues that: “These glamorous noir femmes fatales tend to be women who seek to advance themselves by manipulating their sexual allure and controlling its value…There is, then, a significant ambivalence attached to the ‘erotic woman’: she is fascinating yet at the same time feared… The noir hero frequently agonises about whether or not the woman can be trusted, whether she means it when she professes love for him, or whether she is seeking to dupe him in order to achieve her own ends.” (1991: 63) Due to the femme fatale archetype crossing the line between good and bad, and generally just acting unscrupulously, the male counterpart is often driven to the brink of desperation and left hanging by a thin thread, thereby becoming the fall-guy. Lawrence Kasdan's Body Heat (1981), in which Rourke actually plays a minor part, is a prime example of this and a classic erotic thriller in all aspects; a neo-noir atmosphere, a femme fatale, a fall-guy, and a murder mystery. Obviously a well-tested formula, but it works — plain and simple — and the movie is quite captivating in some respect. Kathleen Turner, the film’s femme fatale, is certainly a slippery entity from the very toes and up. An inversion of roles is not infrequent, however, and the male is also capable of adopting the traits of the femme fatale and in turn become, appropriately entitled, the homme fatale.

One of the fascinating things about Mickey Rourke and his ventures into the land of erotic thrillers and softcore films is the outcome of his interaction with female counterparts, which often leaves him a broken or even dead man towards the end of the flick in question. He is, in the majority of softcore films he has appeared in, the victim of either female power, manipulation, or his own desires, and more often than not with rather fatal consequences. The following two sections will discuss this pattern in further detail.

2. Reaching the Stars in 1986 – Hitting the Bottom in 1997:

“Be careful that victories do not carry with them the seeds of future defeat.” – Sun Tzu 2

Adrian Lyne’s 9½ Weeks (1986) is arguably the most popular film that Rourke has appeared in to date. Although the film has a quite uneven and incoherent feel to it at times, it is nevertheless relevant when discussing softcore cinema, not so much because of the film’s success, but rather because of the way in which it tries to incorporate erotic thriller undertones and turn its narrative into something that desperately tries to be dangerous, transgressive and thrilling.

Even though rumours abounded that Adrian Lyne was in over his head on the film and that trouble brewed in the ranks of the cast and crew, 9½ Weeks turned out to be a huge success internationally, even though it was regarded as a bit of a problem-child by critics and the likes before it was even released.3 Rourke and Basinger both rose to superstardom following its European release, most notably in Paris where it played for two years.4 American film critic Joe Bob Briggs relates: “And then a strange thing happened. 9½ Weeks was one of the first failed movies to become a blockbuster hit…at the video store…when the film was released theatrically in Europe, it went through the roof. In Paris, it played for two years, and it would eventually earn $ 110 million internationally.” (2005: 274) On a funny little side-note, Kim Basinger once stated that the day she met Rourke “…was one of the worst days I’ve ever lived through.”5 and that kissing Rourke “was like kissing an ashtray.”6

The sequel, Another 9½ Weeks (1997), probably sounded interesting on paper, but the actual result basically ended up as a cinematic bottom feeder belonging in the DTV dustbin. The tag-line of the movie reads “On the trail of an old love, he found a dangerous new obsession”7, which was probably intended to recapture whatever it was 9½ Weeks had and bring it up to date, but perhaps the artistic justification of making a sequel eleven years after the first one was just not there. The overreaching script and dialogue certainly leaves a lot to be desired. Even Anne Goursaud, who directed Another 9½ Weeks, could see that something was not entirely working out the way it should in the film, stating that:

It was a difficult movie in the sense that the script never happened, I didn’t pick Angie Everhardt who was not a serious actor, and Mickey [Rourke] looked like Quasimodo. So there were a lot of things to overcome. But, you know, I’m very proud of the work in it. I think it’s a beautiful film. We only had thirty-five days, we had two cities, Vienna and Paris, which we had to make connect – because the story only takes place in one place but we are constantly switching locations. Mickey I think is always good.”8

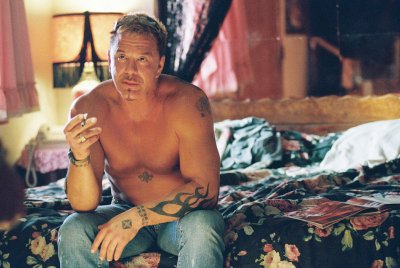

However, despite the negative criticism levelled at the film, it is rather interesting for a number of different reasons. First of all, it is much bleaker and much more atmospheric than its predecessor, 9½ Weeks. Rourke looks beaten up and down-and-out, which adds a certain quality to the film and enhances its melancholic atmosphere. Contrary to this assertion, and in line with how many critics and viewers probably regarded the film, Canadian film critic Christopher Heard is of the opinion that:

There are a couple of things that drag this movie down like a lead weight. One is the fact that Rourke looks rougher than hell – several hundred miles of rough road from the elegant, suave John of the original film…The second big drawback is the exceedingly wooden acting of former model Angie Everhardt. She is fantastic to look at, but this is a story about love lost, longing, regret and dread. To pull that off, you need actors who are comfortable exposing their emotions as well as their bodies. (2006: 107)

The criticism levelled at the film by Heard is certainly valid, but it could be argued that Rourke's physical appearance adds an important depth and layer to the film. After all, he is portraying a man who is mentally scarred due to the loss and absence of the heroine of the first 9½ Weeks, Elizabeth. Since Rourke’s physical appearance in Another 9½ Weeks was not that of the first instalment, not to mention that he had not attained much success with some of the work he had done in the 90s, many viewers may have stopped perceiving him as a star due to his absence from the big screen during that time. As Curtis Harrington points out in an article entitled The Erotic Cinema: “The star, indeed, is very often the personification of sexual attractiveness, and whether stars are influenced by larger social changes or whether it is they, once discovered, who serve to influence society…the fact is that they demonstrate, when extremely popular, the current taste in what is sexually desirable.”9 The idea of cinematic representations of sex being “sold” to the audience on the basis of, for an example, a movie star is touched upon by Tanya Krzywinska and is worth quoting at length: “Potential audiences are often lured by the prospect of seeing certain stars in an erotic context and the reception of a film can be based on the solicitation of sexual or erotic investments on the part of the viewer. For an example, the presence of an admired star might attract a viewer to watch a film in a genre that is not of immediate interest.” (2006: 27) The audience may simply not have associated the Rourke of 1997 with the Rourke of the 80s, which is parallel to what may have happened over time to the cinematic representation of sex; what was desirable in the 80s did not necessarily move beyond its time sphere and carry on well into the 90s. The perception and understanding of certain concepts that were once considered obscene, immoral or perverse often change and move away from the margins where they once belonged. Maybe 9½ Weeks is a good example of this, for as Joe Bob Briggs states: “Perhaps it represented all the bondage, domination, and sadomasochism America could stand at the time.” (2005: 274) Today the film may come across as a bit outdated and downright cheesy to some viewers. Again, perceptions and understandings of certain concepts of sex are rethought and re-evaluated over time.

What both instalments of the 9½ Weeks legacy have in common is that John (Rourke) ends up being the fall-guy, or loser if one will. He is either left by the female counterpart as is the case with the first 9½ Weeks, or he leaves her as is the case with Another 9½ Weeks. The rather ambiguous ending of the latter seems to indicate that he leaves without finding any sort of resolution to his inner struggles, perhaps emphasised by the last thing he tells Lea before leaving: “I don’t want to hurt anybody anymore”, which could potentially signify that he is done playing masochistic tricks on women since it leads him nowhere. The John/Elizabeth and John/Lea couples are adventurous, independent and resourceful, but each affair seems to require a loser at the end. Both films create the possibility that John is the one who loses more than he gains:

9½ Weeks is a feature-length montage of varying sexual encounters between Elizabeth and John, including those in which John positions Elizabeth as the subordinate or masochistic party. Still, the structure of the film moves her from the position of a confused divorcée to that of a woman in control of her choices. (…) Elizabeth’s 'No' to John which concludes 9½ Weeks also resonates through its (female-directed) DTV sequel, despite the fact that the point of view shifts to Mickey Rourke's John…Essentially, Lea becomes John, the role-reversal making plain the sado-masochism of the first film’s relationship, and perhaps suggesting Love in Paris as male-tragic-romantic fiction. This is an interesting premise for an erotic drama marketed on its erotic thriller credentials.10

Even though 9½ Weeks and Another 9½ Weeks are miles apart in terms of success, the quality of both of them is debatable and up for discussion. One could argue that Another 9½ Weeks was, despite its overreaching script, more coherent than 9½ Weeks. When watching 9½ Weeks it is quite obvious that some of the scenes jump inconclusively to others, often leaving large gaps and holes in the chronology and plot of the film. This opinion is echoed by Christopher Heard: “Ultimately, what makes the film so deeply flawed is that each segment has a different look and feel, giving the whole thing a lack of consistency…It was billed as this dangerous, darkly erotic film, but was really nothing of the sort.” (2006: 54) Overall, neither one of the 9½ Weeks films are purely erotic thrillers, but rather melodramas with erotic thriller undertones. Neither Elizabeth nor Lea is in any way a femme fatale since neither of them represents or embodies the characteristics of a classic, genuine femme fatale, but they do nevertheless have a strong influence on John’s regression spiral.

The central theme of both films appears to involve self-development and sexual discovery attained through transgression. This type of narrative framework is touched upon by T. Krzywinska: “Sexual initiation and self-discovery narratives privilege the transition from innocence to experience.” (2006: 63) This resonates quite well with what both 9½ Weeks flicks are essentially about, although the first instalment arguably presents it from a female point of view since the camera follows Elizabeth before and after her relationship with John.

3. Exit in Red – A Generic and Lacklustre Erotic Thriller:

Yurek Bogayevicz's Exit in Red (1996) is one of the more interesting erotic thrillers that Rourke has starred in. Borrowing, incorporating and weaving traits from psychological thrillers and murder mysteries into its narrative, the film is an interesting example of a formulaic and generic mid/late 90s DTV erotic thriller that employs and utilizes all the clichés of the genre, be it the twists in the plot or the stereotypical figures and their interactions. In Exit in Red, the erotic thriller tones are prevalent instead of being subtle or hidden underneath the narrative as is the case with, for instance, Angel Heart and the 9½ Weeks legacy.

In this one, Rourke, who plays a psychiatrist with a major talent for picking the wrong girls, is lured into a dangerous trap set by a femme fatale and her conspirator-slash-lover, which results in him being framed for the murder of the femme fatale's elderly rich husband. It does not get much more clichéd than this. Ultimately, when the femme fatale (Annabel Schofield) and her vicious partner-in-crime (Anthony Michael Hall) end up dead, Ed (Rourke) can only conclude that “I don’t feel much of anything. I’m just weak. Women are my addiction.” This leaves him on a bit of a sad note, but what would a generic erotic thriller be without a weak man who is addicted to risky women and sex-with-fatal-consequences?

Exit in Red is, despite its obvious lacks here and there and the inability of some of the actors to seem anywhere near convincing, quite interesting in an analytical perspective and in comparison with other DTV erotic thrillers from the latter half of the 90s. Rourke’s performance is impressive, certainly taking the dialogue and script that he had to work with into consideration, but otherwise the film leaves a lot to be desired, even though it could potentially have turned out better had it not tried to appear so layered and complex while in actuality being thin as a wafer and without much of a climax. It serves as an interesting example of an erotically charged film which rests on a well-tested formula, but which ends up being a tad tedious and somewhat uneven. It simply comes across as too generic, too average and too unoriginal, but it is nevertheless an interesting piece when viewed from an analytical angle, especially in conjunction with femme fatale and fall-guy archetypes.

It is worth noting that the majority of softcore films in which Rourke has appeared rarely ever focus on subjects such as infidelity, adultery and marriage. This does not entail that there are no transgressions in these films, but they certainly differ from a large body of other erotic thrillers with respect to subject and theme. To line up a few examples, one could argue that the 9½ Weeks films are about sadomasochism, sexual self-discovery and personal development; Angel Heart has a trace of incest that forces the viewer to re-think the whole narrative once it reaches its end; Wild Orchid is basically just about a young single woman who is drawn to a mysterious, frigid man named Wheeler (Rourke) who specializes in setting up kinky sex games, but the film appears (and there is an emphasis on “appears”) to be about sexual discovery and awareness rather than anything related to socio-cultural issues such as marriage and adultery; only Exit in Red toys a bit with infidelity and adultery, but the manner in which they are represented in the narrative clearly indicates that they are less essential to the plot.

4. Erotic Thrillers, Softcore Films and Censorship in the US:

Censorship and the MPAA rating-system are highly relevant when discussing cinematic sex and its development throughout film history. Erotic films basically date from the inception of film production itself, an early example being Edison Company’s The Kiss (1896).11 A direct influence on the erotic thriller genre was the wave of noir films made during the 1940s and 1950s, which often had (pre-)erotic thriller undertones in terms of subject, theme and archetypes; seductive and manipulative femmes fatales, fall-guys, decoys, murder mysteries, and hard-boiled detectives. As with erotic thrillers, film noir was often centred in a world of crime and the former genre does owe quite a lot to film noir, not only because it rests on a foundation laid out by film noir, but more importantly because both genres operate with themes that have the ability to attract, captivate and provoke viewers. The fact that film noir has provided a framework for more contemporary genres such as the one dealt with in this article is perhaps better understood when taking the tools both genres operate with into consideration. Frank Krutnik states: “The seductive power of the ‘noir-mystique’ has persisted to the present day. The less that is explained, the more there is that attracts: this is the basis of its seduction.” (1991: 28)

Not surprisingly, politics has a significant influence on what is produced, distributed and shown on the screen in the US. The more contemporary relation between US politics and cinematic sex is picked up by Linda Ruth Williams who states that: “Hollywood doesn’t do sex like it used to. A pervasive puritanism infiltrated the industry in the new century, particularly after the election of George W. Bush, putting the erotic back in the closet along with a range of other so-called ‘progressive’ cinematic concerns.” (2005: 417) Sex in cinema is obviously a controversial issue and since cinema operates in the public sphere it is, in one or more ways, influenced by cultural, political and economic factors. It is worth quoting Charles Lyons' “The Paradox of Protest” in trying to supply the reader with a short and precise overview of censorship and its relation to the US film industry: “Throughout the history of the American film industry, sexual words and images have provoked more censorship and group protest than any other subject. Charges of “obscenity” and “pornography” have repeatedly thrown religious leaders, industry regulators, studio and independent producers, and state and local officials into heated disputes over what the limits of cinematic treatment of sexual subjects ought to be.”12 In the context of film censorship, a film can be subject to re-editing, removal of certain scenes, or, in worst-case-scenario, withdrawn without ever seeing the light of day. Linda Ruth Williams relates:

The history of sexual representations has developed in tandem with mutating moral, public and industrial codes. Sex and violence continue to be the key anxieties of the censor. Like noir, the erotic thriller has both. Like noir, the erotic thriller mixes sexual spectacle with violent thriller plots, and combines neo-noir narratives with extended moments of explicit eroticism…The closer to the wind of censorship a film sails, the more primary sex becomes at the expense of crime. (2005: 36-37)

The erotic thrillers and softcore films that Mickey Rourke has starred in, and that have been mentioned in this article throughout, received the following certifications and ratings13:

- Body Heat (1981) – USA: R

- 9½ Weeks (1986) – USA: R

- Angel Heart (1987) – USA: X (original rating)

- Wild Orchid (1990) – USA: R

- Exit in Red (1996) – Rated R for strong language, violence and some sexuality. (MPAA)

- Another 9½ Weeks (1997) – Rated R for strong sexuality and some language. (MPAA)

Apart from Angel Heart, the certifications and rating of the above examples indicate that there is nothing that is really out of the way in terms of perversity, transgression or strong sexual content in them. Linda Ruth Williams ties an interesting comment to the R-rating in the US: “Sometimes the perception of mainstream tolerance is articulated as a classification barrier: a film containing nothing hotter than softcore sex will receive an R or NC-17 rating in the US…” (2005: 267) According to Joe Bob Briggs, Wild Orchid “…had to be drastically edited in America to get an R rating, resulting in a limited release.” (2005: 289) Angel Heart did manage to receive an R-rating in the US just before release: “A scene featuring Mickey Rourke and Lisa Bonet having sex was slightly cut by around 10 secs before release in order to avoid an X rating. The European theatrical version and US video version restore the missing footage.”14 The scene between Rourke and Bonet is probably the most controversial sex scene Rourke has ever participated in on the screen, followed by the climatic sex scene in Wild Orchid.

Cinematic sex is controversial in the sense that it often contradicts with certain moral norms and codes within society, as T. Krzywinska also refers to: “In presenting what is expected to be privately intimate for mass consumption, making money out of it, and the act of making sex a spectator entertainment, the representation of sex in cinema challenges some of the basic principles that are perceived to order a civilised society.” (2006: 83) As to the rating-system, one could be tempted to think that if you prohibit X, you increase the desire for it and thereby create what may be termed a cookie-jar effect. This is not necessarily so, but the ratings do carry very little information and, without claiming this to be true, the system does not appear to be an entirely consistent enforcement, and whether it serves the purpose it set out to do in its inception is a whole other discussion.

5. Erotic Thrillers in the Overall Perspective: Still Alive…and Well?

The question that keeps popping up while doing research on the erotic thriller genre and soft-core cinema in general is: why did the genre not thrive? It became more of a cinematic subculture throughout the 90s, gaining a strong position in the field of VHS and DVD releases. As Linda Ruth Williams states:

The direct-to-video erotic thriller occupies a unique space at the birth of a new set of viewing patterns which transformed cinema in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Its case reveals a complex and sometimes confused relationship to both genre and audience: part-porn, part-film noir, all ‘B’-movie, a hybrid form dripping with the symptoms of our anxieties and pleasures.” (2005: 249)

There is no unequivocal answer as to why the genre did not continue to thrive within mainstream cinema. One major blow to the mainstream softcore industry could very well have been that people just became fed up with its releases: the dividing line between repetition and variation became too thin and some viewers probably felt that erotic thrillers and softcore films became too predictable and outworn plot-wise.

The difference between softcore and hardcore films is also a factor that has to be taken into consideration when discussing the ebb and flow of the erotic thriller genre and how it manifested itself in cinema. Softcore sex is practically everywhere in cinema regardless of genre. The audience may have found softcore sex scenes too implicit to ever come across as downright sensual, stimulating and erotic. They are aware of what is going on in the sex scenes, but they never see any penetrations and the sex scenes are faked and stimulated. This could be one of the reasons why softcore films were left out in the Hollywood cold over time. Nudity in PG and R-rated films is at times blurred or put in the background by lighting or camera-movements, so the visual sexual content often rests on implication. Viewers are forced to infer the rest due to the sex-scenes often falling victim to ellipsis, gliding from scene A to scene C with scene B being implied by the events in scenes A and C. However, using ellipsis also has an advantage, as pointed out by Tanya Krzywinska: “…one of the strengths of the ellipse is that it allows the viewer to project into the gap their own personally tailored fantasy.” (2006: 29) There is a limited acceptance of what can be shown in softcore films and the cultural filters they inevitably have to pass through differentiate them from hardcore sex films. There is a limited acceptance as to what is tolerated in softcore films.

Bringing Rourke back into this discussion, why did Another 9½ Weeks and Exit in Red end up in the sale bins of video stores? Were they completely devoid of any potential at all? The answer could be that neither of the two was able to deliver what they essentially promised they would. The same goes for Wild Orchid and Fuck The World (AKA The Last Ride). If these films serve as different examples of erotic thrillers and softcore films made during the 90s, an interesting development of the genre can be traced throughout the 80s and 90s, which indicates that the attitude towards sex on the screen shifted during the early 90s. Continuing this point of discussion, Walter Gernert, who is an executive producer of quite an impressive number of erotic films15, offered an interesting explanation when asked why the genre did not thrive:

Well, if you look at the history of sex on film, there’s been this slow but steady concentration of what is it really there for. And, in the end, what it was there for was titillation. The more you dress the pig up like a lady the less the people liked it. And now, the porno industry went from six-figure budgets shot on 35-mm film with horrible scripts but attempts at filmmaking, to today where probably the average budget is a tenth of that and it’s simply nothing but sex. The same thing gradually was happening with erotic thrillers. The pretext of real storytelling and filmmaking gradually gave way to what the viewer really wanted to see, which was an excuse to be titillated.16

Hardcore films gained more ground and gradually took over what was once a premise of softcore films and erotic thrillers. Porn does not possess the same restrictions as erotic thrillers and softcore films do, which could be a part of the answer as to why the latter type of films became more of a DTV subculture throughout the 90s.

Using Jane Campion's In the Cut (2003) as an example of a contemporary erotic thriller that has been able to challenge the image of Hollywood's increased Puritanism, L.R Williams sums up the current state of the genre by concluding that: “The erotic thriller is by this account both alive and dead; a form which has consolidated itself into a safe, known product, which has performed both well and badly at various levels of the market, and one which perfectly exploits the contemporary cinematic afterlife of video and DVD.” (2005: 420) On a little side note, Rourke's name actually came up in connection with the casting of In the Cut, but he was shelved by Nicole Kidman without the two of them ever having met.17 Her decision was obviously rooted in Rourke’s often publicised bad-boy image and hellraising-Hollywood-hardman attitude. Understandably, Rourke was not too pleased with this decision: “I don't know why. And she's never even met me! But there was nothing I could do, because Nicole has much more influence than I do.”18

There are without doubt viewers who crave that element of the familiar and repetitive, which probably also accounts for why the erotic thriller genre continues to exist in the margins of cinema. Rourke’s line of work within softcore cinema throughout the 90s is undoubtedly testament to the fact that films who stick to certain formulas do not always pan out so well.

6. Final Thoughts:

What this article has hopefully brought to the forefront is that the erotic thriller genre is so large in scope that it is nearly impossible to make a detailed account of all the various social, cultural, political and economical factors that are interrelated with the genre: gender issues, censorship, sexual identity and film noir are all connected in one or more ways to how sex is represented on the screen and how erotic thrillers and softcore films are perceived by the public. Whether the genre will ever undergo a transformation and perhaps even experience resurgence remains to be seen. Where it all goes from here, nobody really knows and one can only speculate, but it will certainly be interesting to watch the twists and turns of the genre in the future. Sex in cinema has a seductive power and an ability to provide the viewers with images that are able to match some of their own personally constructed ideas and fantasies about sex. The erotic thriller genre and softcore films in general will probably never cease to withhold a seductive power over certain audiences.

As to Mickey Rourke, even some of the films in which he has appeared that have not been touched upon, discussed or mentioned in this article are relevant when discussing how some of the characters he has portrayed tie in with masculine culture and male power, as well as the notion of the fall-guy. Although not an erotic film by any stretch of the imagination, the highly successful and brilliantly executed Sin City has Rourke portraying a lovelorn brute who truly feels emotional pain. When asked in an interview what Rourke himself thought of being the most love-stricken character in the film, he replied: “I didn’t really think about it much that way. I did, it sort of nauseated me. I hate that feeling.”19 Certainly an interesting comment from an actor whose career has partly been shaped by starring roles in erotic thrillers and softcore dramas. Although only mentioned in passing throughout this essay, Fuck The World (1994) is a peculiar little film with a very good cast and an interesting storyline involving an ex-con (Rourke) who falls in love with an outlaw woman (Lori Singer). Without giving too much away, the ending of the film ties in with what may be perceived as a tragic love-story where the outcome is of relevance when discussing the pattern of Rourke's involvement with the opposite sex that has been discussed throughout this article.

Rourke should not be overlooked when trying to map out the ebb and flow of the erotic thriller genre in the US and its key-players. Films such as Wild Orchid, Fuck The World, Exit in Red and Another 9½ Weeks are interesting in an analytical perspective and provide an interesting framework for discussing the way in which sex has been represented on the screen from the late 80s till the late 90s. Trying to tie Rourke in with a more general overview of softcore cinema and its relations to censorship, the rating system, and film noir, has hopefully provided an interesting take on the erotic thriller genre’s narrative blueprint, its patterns and conventions, and the myriad of different powers beyond the genre itself that have added weight to it over the years. Speaking of weight, the final question that this article wishes to pose to its readers is: How much weight can the erotic thriller genre actually bear and how much can one read into it?

7. Notes:

- Linda Ruth Williams, The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2005) p. 97.

- This quote is taken from: Christopher Heard, Mickey Rourke High and Low, (London: Plexus Publishing Ltd, 2006) p. 87.

- Joe Bob Briggs, Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History, (New York: Universe, 2005) p 274.

- Briggs, Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History, p. 274.

- Briggs, Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History, p. 278.

- Briggs, Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History, p. 279.

- See http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0092563/alternateversions

- Williams, The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema p. 410.

- Curtis Harrington, “The Erotic Cinema”, Sight and Sound, 22:2 (1952: Oct./Dec.): p. 67.

- Williams, The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema, p. 392.

- Edison Company’s The Kiss is an example from: Tanya Krzywinska, Sex and the Cinema, (London: Wallflower Press, 2006) p. 2.

- Charles Lyons, “The Paradox of Protest”, In: Movie Censorship and American Culture, Ed. Francis G. Couvares, (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press 1996) p. 280

- The ratings are all taken from each film’s respective profile on www.imdb.com

- See http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0092563/alternateversions

- See Walter Gernert's filmography at http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0314628/

- Williams, The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema, p. 69

- Christopher Heard, Mickey Rourke High and Low, (London: Plexus Publishing Ltd, 2006) p. 125.

- See http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0199626/news

- http://www.indielondon.co.uk/film/sin_city_rourke.html

8. Bibliography:

8.1 Books and articles:

- Austin, Bruce A. G-PG-R-X: The Purpose, Promise and Performance of the Movie Rating System. Journal of Arts, Management and Law 12.2 (1982): 51-74.

- Briggs, Joe Bob. Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History. New York: Universe, 2005.

- Couvares, Francis G. Movie Censorship and American Culture. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996.

- Doherty, Thomas. Pre-code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930-1934. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- Harrington, Curtis. “The Erotic Cinema”. Sight and Sound. 22:2 (1952: Oct./Dec.): 67-72.

- Heard, Christopher. Mickey Rourke High and Low. London: Plexus Publishing Ltd, 2006.

- Krutnik, Frank. In a Lonely Street: Film Noir, Genre, Masculinity. London: Routledge, 1991.

- Krzywinska, Tanya. Sex and the Cinema. London: Wallflower Press, 2006.

- Williams, Linda Ruth. The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005.

- Zare, B. “Sentimentalized Adultery”: The Film Industry’s Next Step in Consumerism. Journal of Popular Culture 35.3 (Win) (2001): 29-41.

8.2. Websites:

- Corliss, Richard. In Defense of Dirty Movies. Time Magazine. July 05, 1999.

- Foley, Jack. Sin City - Mickey Rourke interview.

- “The Femme Fatale”. No Place for a Woman: The Family in Film Noir. First posted: January 1996, last updated: April 1999.

- Mills, Michael. High Heels on Wet Pavement: Film Noir and the Femme Fatale.

8.3 Films (arranged by year of production):

- Body Heat (1981, directed by Lawrence Kasdan)

- 9½ Weeks (1986, directed by Adrian Lyne)

- Angel Heart (1987, directed by Alan Parker)

- Wild Orchid (1990, directed by Zalman King)

- Fuck The World. (1994, directed by Michael Karbelnikoff)

- Exit in Red. (1996, directed by Yurek Bogayevicz)

- Another 9½ Weeks. (1997, directed by Anne Goursaud)