This text has been submitted as an original contribution to cinetext on December 23, 2005.

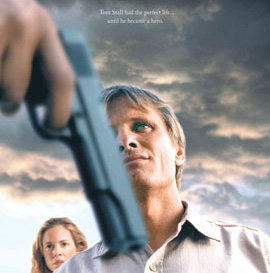

A History of Violence Film Analysis

|

|

by Richard Stanwick |

In the Cain and Abel myth, god favors the hunter Abel who is consequently killed by his first born brother Cain, the technological farmer. This reverses the usual psychological understanding and prejudice since the first born Cain inverts and assumes the role of the traditionally resentful saboteur second son.

Whereas elsewhere in the Middle East god consented to and blessed the transition to agriculture from hunting, in Genesis the Cain myth maintains a recalcitrant echo of man’s failure to be released from the burden and obligation of loyalty to a warrior god

In Genesis’ god’s view, man’s drive and desire to become godlike are declared to be intolerable, unforgivable and punishable by death, although only expulsion and pain are actually imposed. In HOV, Cronenberg provides a hint concerning the outcome of man’s transition from Pisces, the fish god who is sacrificed on his journey home, to our current house of Aquarius which Jung linked to a created technological monster. I speculate or perhaps submit that in his projection of man, the course and trajectory of the technologically created monster remains rooted in his tradition, physically and culturally, and is mired in a historical blindness that leaves his future chained to Cain’s curse.

In HOV, the hero’s journey is reconstructed from the middle. His postmodern displacement remains entrenched in the quicksand of historical violence which he refuses to acknowledge. When confronted as to the origins of his violent past and his own misdeeds, Cronenberg depicts him as a lost child who repeats Jesus’ answer when confronted by the question of TRUTH. But unlike Jesus, Joey Stall Cain seems to have forgotten his past and feeds on self-deception.

It may be tempting to pursue elsewhere some rather obvious political echoes and analogies such as the history of involvement of the US with destruction, violence and oppression in other nations, its habit of deserting its stated policies, denying its culture of death and then withdrawing to its own backyard while projecting blame unto others. When vengeance is returned, it recoils in horror and responds with yet greater terror lashing out without justification on the grounds of self-defense lest its motives of control/power become exposed. The façade of folksy normality must be maintained.

HOV’s psychological components add to the mystery. The discrepancy of his former killing self known by the child-like name of Joey and his mask of Tom Stall (a play on his stalled psychological state and the German sounding word steel) accentuate the original unacknowledged violent sin of Joey Cain.

Although he is married to the law, he neither understands it/her, nor his family. This hero’s lack of relation to and detachment from his violent past and his seemingly mysterious memory loss of his origins depict the American mode of reflection and analysis through a self-deceptive narcissistic lens.

In staging various confrontations to Tom’s status in the house of the hidden monster or against the agricultural background (Abel’s corn field) Cronenberg keeps reminding us of Cain as the modern agricultural killer of the hunter brother/history/tradition.. The framing of a small simple agricultural town against the unknown dangers of Philadelphia and Boston helps to confirm the delusional state of fragmented America. Abel, the overt hunter is deformed by techno Cain by means of a razor wire in an attempt to blind him into a similar narrow stance. Abel is ultimately killed along with his cohorts to demonstrate that even historical roots require uprooting to prevent the (re)emergence of consciousness of god’s curse against the killer who is doomed to wander without meaning. The curse of violence pervades his house as even his reluctant son emerges as a destroyer and potential killer when his docile mask is exposed by an aggressor. Contra Oedipus, he eventually saves his father and inherits his damned bounty by becoming a killer himself. Here damnation is shared and perpetuated by family.

Tom’s reflexive but studied expertise in killing reminds us of his origins. He stems from Philadelphia (the love of the ambiguous oracle of Delphi). Quite simply, he is ambivalent with respect to his origins. He shares his brother’s partial origin from Boston hinting at the rebellious Boston tea party. Here violence is not only natural but constitutes the defensive ticket to prevent the truth from overpowering his self deceptive mode. His Delphic roots of uncertainty and displacement in the world cannot be overcome because he destroys not only to overcome others but also in order to hide from himself. In American mythos, revelation comes mostly from the misreading of ancient books/history.

At the end, after the ritual annihilation of his past, the hero’s return home to dinner presents him an opportunity to deal with the emerging truth. His familial reward is an empty plate and a place at the traditional table but the option of change (by refilling his plate anew) is rejected. Inexplicably, the American mode of conflict resolution remains unchanged in a recurrence of static reverberation. The repressed status of the history of violence maintains the delusion of goodness which is propped up by lies but is paradoxically governed by self deception. Violence, the preserve of the hunter god continues its reign among the purported pure and innocent. Man cannot or is unwilling to come to terms with his drive to become god-like and is cursed to destroy without apparent motive. Tom is indeed displaced.

The Freudian nexus of sex and aggression is staged appropriately on the stairs. At least C does not glorify or edify it by having the climax delayed by incremental steps. The option of urging her upward the stairs could have highlighted the union of sex, death and aggression at some predictable zenith reaching nowhere. In C’s view, the woman (here the law) remains bound to the aggressor and as Nietzsche postulated, woman always loves the warrior in man and submits to him in his quest to conquer.

And so we have Cronenberg’s answer to the question of what constitutes truth. American Joey is cursed and displaced by his history of violence and remains grounded in aggression, sex, doubt, fear and death with no way out because he, like Oedipus is blind, crippled and incapable of seeing himself as he is. Isolation only reinforces his detachment to the curious question of the truth of his nature.

And C suggests that it appears to be no acceptable path from this monster’s house except through periodic venting and release to alter/destroy the outside and those who differ from the ambivalent pure blond boy beast. And so, Joey the steely Cain has not learned that even though god approves of the man/hunter’s aggression and its resultant death and sacrifice of animal, he curses technological/agricultural man and displaces him when he kills his brother. Since vengeance remains in god’s domain, man is obliged/expected to sublimate his aggression. But even in god’s land of vengeance and death, Joey the child continues to challenge and demand god’s right to kill.