Weight Watching: Method Acting as a Label and Subtext in The Machinist

|

|

by Joerg Sternagel |

1. Acting in Oblivion

The broad and close analysis of acting in film represents a hitherto neglected area in film studies. As Michael Peterson aptly remarked in his contribution to an analysis of Martin Scorsese’s highly-acclaimed and intensely-discussed film Raging Bull from 1980, starring method actor Robert de Niro as prize boxing champion Jake La Motta, »performance studies can offer film studies much«. (1)

Each attempt in analyzing acting in film raises a set of questions which are both essential to academic discussion and research, and, as Peterson stresses, far from being answered easily: »How can the subtext of acting be defined?«, »What constitutes screen performance, acting on and for the screen?«, and »To what extent do single actors or ensembles, associated to the work of directors, function as authors?« (2)

2. Acting in Film

The core aspect of the interrelation between the performance of an actor as staged and set in scene for the screen and the event of watching the performance as experienced by the viewer has to be acknowledged in analyzing contemporary screen performances and their effects on modern-day (western) culture. In front of the screen, the viewer is confronted with the image of a dynamic film creation reaching him or her through the representation of the moving bodies of the actors, a process James Naremore describes by suggesting to work with the term »acted images«:

Clearly films depend on a form of communication whereby meanings are ; the experience of watching them involves not only a pleasure in storytelling but also a delight in bodies and expressive movement , an enjoyment of familiar performing skills, and an interest in players as . (3)

Where meanings are »acted out« and »acted images« are created in the process of filmmaking, or in other words: where performances are set, the enjoyment of the spectator watching these performances on screen, in the final cut, indeed does not exclusively lie in the pleasure of following the plot, but in watching the actors themselves and their performances.

But for understanding acting in film and its aesthetic effects, it does not appear to be sufficient to analyze the actor and his or her role as a star or to sum up certain mannerisms the spectator has been getting used to watch. Moreover, scrutinizing the form of communication, as Naremore suggests, serves as a starting point for analyzing acting in film.

Numerous studies on stars, especially in works on American film, and the uncountable biographies of actors and actresses stress the marginal or non-existent consideration of acting itself. Close research on acting in film has been a rather neglected area in film studies, or, as Pamela Robertson Wojcik points out: »There is much popular discourse about stars and film roles ... But despite the attention to actors, there is little popular discussion of in movies.«(4)

3. Setting Performance and Watching Performance

An analysis of acting hereby should focus on the body, the corporeality of actor and spectator or, as Vivian Sobchack puts it: »[We, the spectators, will have] not only to watch, but to scrutinize the [the actor’s ] body ... [We’ll have] to think through it.« (5)

Within the frame of obligatory differenciation between the image as imagination and the picture as a form of representation, the spectator, as Sobchack remarks, faces an immediate experience of the image developing more and more corporeal.(6) In this context, it has to be stressed that »acts of imagining and not perception are also central in viewing films«. It is essential to acknowledge the immediate experience of the image and everything behind. The medium film is therefore an efficient creator of imaginary elements, or, as Winfried Fluck notes, this medium is »wonderfully effective in mobilizing and articulating imaginary elements, from individual effect to trauma, and in hiding them, at the same time, behind the immediate experience of the image«.(7) An analysis of immediate experiences created by images invites us to closely focus on the body and its perception: Immediately, we, as spectators, may ask how the actor’s body can be thought through by us. In her latest book »Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture«, Vivian Sobchack uses the opening sequence of Jane Campion’s film The Piano (1992) as an example to describe her own perception: The fingers of actrice Holly Hunter, as seen in the first minutes of the film, playing the piano, awake the awareness of the viewer’s, Sobchack’s, own fingers: What did her fingers know, feeling the kinesthetic subject, and having a vision in the flesh. (8)

Giving a brief historical overview, the author points out the acknowledgement of the body and sense perception by former film theorists: Siegfried Kracauer stressed the cinema’s ability to stimulate the viewer’s awareness of his or her physiology and senses; Walter Benjamin focused on aspects of the viewer’s sensuous and bodily perception; Peter Wollen had strengthened the argument of Sergej Eisenstein who dealt with the synchronization of the senses in his work on film. With her phenomenological analysis, Sobchack deeply relies on the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty and his approaches to the perception of the body, operating with basic arguments of his main work from the 40s, »Phenomenology of Perception«:

My body is not only an object among all objects ... but an object which is sensitive to all the rest, which reverberates to all sounds, vibrates to all colours, and provides words with their primordial significance through the way in which it receives them.(9)

One has to take into account the interaction between »mind« and »body«; the body has to be recognized as a »subject« that »perceives and thinks«. Consciously dealing with the acknowledgement of an interaction between actor and spectator, between the set performance and the watched performance, different trends and traditions in contemporary film performance can be closely analyzed. In this overall context, the forms of communication and their different visualizations and realizations define the subtext of acting in film and constitute acting for the screen.

4. Weight Watching

Starting with an analysis of »material elements of the actor’s performance«, American director Brad Anderson’s debut The Machinist from 2004 eventually emphasizes the above mentioned approaches. (10) This work teaches us, atfirst glance and experience, to watch the protagonist Trevor Reznik (Christian Bale) losing weight: »If you get a little thinner, you will not even exist anymore«, two women, namely Stevie (Jennifer Jason Leigh) and Marie (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón) confront Bale’s character, the »machinist«, with his physical condition in the first twenty minutes of Anderson’s Mexican-American film.

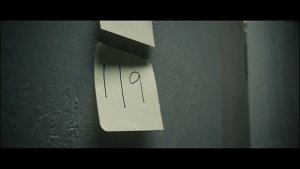

The film features Christian Bale who was born in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, Wales in 1974. He debuted on the London West End stage supporting the comedian Rowan Atkinson in the mid-80s and started his career as a film actor in Steven Spielberg’s World War II epic Empire of the Sun (1987), co-starring John Malkovich. Bale played a boy named Jim facing the war in Shanghai in the early 40s. In The Machinist, Bale apparently shows a shocking preparation for and performance of the role as factory worker Trevor Reznik who commits a hit-and-run, a deed he cannot bear and therefore suffers from insomnia, corresponding weight loss and further neurotic symptoms like excessively washing hands more than regularly with bleach or writing daily duties on post-it-notes. Being confronted with the rather extreme physical (and psychological) condition – watching Reznik’s development in a long flashback, as seen in the photos beneath, we learn he looses from 134 to 119 pounds – the above-mentioned questions on understanding acting in film arise.

Approaching acting in film in general and Christian Bale’s performance in particular, as already shown, certain introductory considerations have to be kept in mind: Performances are to be seen as filmic elements that create meaning and emotional effects. In this overall context, the material elements of the actor’s voice and body contribute to the final visualization of the character. (11)

Christian Bale’s body can be »thought through«: The viewer is guided not to watch, but to scrutinize his body. Therefore, I suggest to work on a close analysis of the corporeality of the actor’s body, acknowledging the connection between actor and spectator in a system of energy transference seeking to optimize the effect of a direct, immediate experience. Within this system, the actor manages to refigurate the imaged body and simultaneously achieves the resensitization of the spectator’s body.

In this film, the actor shows the authentic being as a performative being that is immersed and culturally mediated »in the social conventions and textual productions wrought by history and culture«. (12) He seems to be driven to »unlikely lenghts in the name of work«, so that »the real pleasure in Anderson’s film lies in the way it slowly comes into focus, as both Trevor Reznik/Christian Bale and the audience gradually come to find meaning in his tortured view of the world around him.« (13)

The actor’s method of »weight watching« for »weight losing« shows a metamorphosis of an authentic being into a performative being.

Strongly committed to a series of films which is described best with attributes like »mysterious«, »psychologically motivated«, and »thrilling«, Brad Anderson directs his protagonist through a dark, shabby and therefore not at all colourful modern-day American city (it may be Los Angeles). The dismal radiation of the city surrounds his sufferings and adds to the impression of a never-ending sleepless voyage of an identity in crisis.

Ascribing The Machinist to a genre-like category: the »mystery thriller«, it seems apparent that the mise-en-scène, the narrative, the lead characterization and performance of this film resemble a common approach of many contemporary (most of all younger American) directors: The films are produced in a fashion that is highly stylized and extremely psychologically grounded. Most of the works do not follow a straight and chronological narrative and appear to be of a disturbing aesthetics, leaving the spectator impressed and stressed at the same time. (14) Two of the most important influences are elements of the cinema of director David Lynch and – especially since the 1990s – the universe of film noir and neo-noir. In the 1990s, these elements were influential on the works of directors such as Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct (1991) and David Fincher’s Seven (1995). Since the turn of the century, this tradition has been succeeded by films like Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000), The Machinist, Don’t Say A Word (Gary Fleder, 2001), Spider (David Cronenberg, 2002), Identity (James Mangold, 2003), Twenty-One Grams (Alejandro González Iňarritú, 2003), The Jacket (John Maybury, 2005), and, last but definitely not least, Session Nine (Brad Anderson, 2005).

Watching both sequences of the »weight watch« throughout The Machinist and a selected panorama of Bale’s performance throughout the film, by focussing on every single still, it becomes apparent that the spectator is literally forced to watch the actor’s weight, or to be exact: his loss of weight. Bale and Anderson constantly present the character as someone who is suffering. Their protagonist is permanently set in half-light, emphasizing the condition of his body. Nakedness is the first apparent means of the performance.

The actor’s body is shown from different perspectives in different actions, and is very often placed in interiors associated with hygiene: the bathroom, and sex: the bed. As mentioned above, the character is supposed to have a neurosis concerning his hygiene: Standing in front of a washing facility and a mirror, the process of excessively washing hands immediately appears to be a ritual that is repeatedly shown in the film. Facing the mirror hereby serves as a means to strengthen the impression of the character’s pain and suffering: Reluctantly, we accompany his voyage and observe his decay while watching his close self-examination in front of his reflection in the mirror.

The actor’s regular undressed state, being mirrored for a close perception, and the manner of the camera, running in a patient motion, teaches us to watch his weight and forces us subconsciously to count his bones. In his role, we learn, the protagonist’s only social contact is the sexual relationship with the prostitute Stevie, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh as a variation of a nurturing woman from a film noir who cares for the insomniac. Facing the character’s physical condition through the eyes of Stevie, enlightens us to be sure of his condition, to closely watch his weight and to be increasingly forced to count his bones. Unwillingly, we experience a transference of energy: the decay of the character and actor is presented in such an extreme fashion that we are forced to get used to watch and, finally, to scrutinize his body performance. We become part of a direct and immediate experience and thereby recognize the implied subtext of acting in this mesmerizing film. Cinematic tension is here created by a focus on the body and the physical action of the body; it is not at all a cinematic tension created between the physical display and the verbal construction that defines this film. Therefore, this work represents an unique example for analyzing acting in film, its constitution and its effect.

The body and the actor’s use of it, his (and the director’s) decision for a corporeal way of acting, mark an apparent subtext of this film.

Regarding the marketing strategies following the release of Anderson’s motion picture, enforced by the production company »Tartan Films & Video« and especially efficient on the film’s DVD release, the art of Bale’s acting was pushed as the work’s primary subtext and label. Consider the meanwhile established phenomenon of a film’s commercial breakthrough success on global DVD markets, as opposed to its commercial failure in national and international cinema releases, which is also the case with Anderson’s film: The Machinist was not released in German theaters and did not run in British theaters for long, but has established as a bestseller (both rental and sale) on DVD in Germany and the UK. A close analysis of this phenomenon, concerning many European and American low-/middle-budget and non-major works, would be worth a single and close examination. First introductory thoughts, concerning this development, starting in the 90s, can be found in the work of Jon Lewis. (15)

In Anderson’s film, the strategy of »method acting« in Bale’s performance is both the predominant subtext and label appearing on stickers of theatre posters, DVD covers and booklets and, therefore, supports advertising campaigns of stores like Virgin and Tower Records. The most common slogan appeared to be »Christian Bale in The Machinist, [it’s] Method Acting Madness!«. (16) But, is there a »method« to the character’s and the actor’s »madness«? How can the subtext and the label of acting in general and of »method acting« in particular be defined in this case? What does this acting strategy have in common with the art of »method acting«? (17)

Bale’s performance apparently focuses on the body and the physical action of the body that, in a direct and immediate fashion, teaches and forces us to closely watch his loss of weight and to be further forced to literally count his bones: »Ravaged by fatigue, his body is little more than a bag of bones. Wracked by exhaustion, his weary mind increasingly plays tricks on him.« (18) It is the physical state, the »fatigue« and the »exhaustion«, caused by the psychological state of guilt, the »insomnia« and the »neurosis«, that determines the subtext of acting and the film’s narrative motivation. We are forced to experience an actor’s extreme struggle for unity in the characterization of his role and may, indeed, be tending quickly to acknowledge this struggle as a subtext of an acting style defined and labelled as »method acting«.

5. Setting Performance and Watching Performance

Acting styles in film, when defined by the short term »method acting«, generally have one approach in common:

Every motivation of building a character and creating a role is based on the actor’s psyche and the character’s psychology. Consider the early ideas and ideals of Russian acting teacher Konstantin Sergeevič Stanislavskij (1863-1938), a stage actor and director, who stressed the creative process of the actor’s work initiated by operating with elements of the actor’s personal memory to reach a liveliness of the created role. (19) In different ways, the actor creates a recourse on feeling, emotion, and memory, helping him or her to create a role of faith, belief and conviction. Styles of method acting, therefore, identify »the actor’s own personality not only as a model for the creation of a character, but as a mine from which all truth must be dug«. (20)

Note the emphasis on different »styles« of method acting, as there is not only one method, but multiple methods that, nevertheless, have some approaches in common, most of all the psychological motivation in approaching a role. Regarding most of the texts dealing with method acting, it is a common error to speak of one method, especially if there is only question of Lee Strasberg and the Actor’s Studio. There exist different schools and philosophies of method acting, among others, Stella Adler, Sanford Meisner, and Sonia Moore. Common techniques of method actors combine physical with psychological exercises, all created and trained for the »truthful« creation of a role. Ranging from the use of the technique of the »affective« or »emotion memory« to the exercise of the »magic if«, the method actor establishes a set of significant acting elements contributing to the identification and acknowledgement of the acting style as a method. The technique of affective or emotion memory, for example, deals with the activation of the actor’s personal memory and the use of it for creating a role. The technique of the »magic if« is simply explained by the question: »What would I do if I were my character in this situation?« Further techniques functioning within the process of creating a role are the one of »public solitude« and »substitution«.

The set of significant acting elements develops a subtext of which the spectator may fastly be fully aware: The expressive quality of every single »acted image« culminates into a rhythm of »expressive coherence«. (21) Initially, the spectator joins a process of intense emotional flow where he or she experiences aesthetic effects of the presented acting technique; a technique he or she, at least in this case, assumes to be part of method acting. Watching this flow, the received impression for the spectator is supposed to be a unity that is formed by the created lifelike images. While the film or rather: the narration passes on, the (method) actor can be joined struggling to create a series of lifelike images in order to create and to form an emotional flow: » ... the real difficulty is the actor’s attempt to sustain emotional , preserving analog changes of mood (...)« (22) Such a flow is commonly identified with styles of method acting and immediately leads to the subtext of method acting – a subtext that can also be realized by assuming the actor’s dense creation of a character’s personality profile, inspired by and developed from the own personal profile.

Watching The Machinist, we are forced to experience an actor’s extreme struggle for unity in the characterization of his role. We closely watch his loss of weight. The actor Bale and we, the spectators, meet in a close interrelation: His performance, as staged and set in scene for the screen, correlates with the event of watching the performance as experienced by us, the spectators, in front of the screen. We face the image of a dynamic film creation reaching us through the representation of Bale’s moving and maltreated body.

As a methodological concept for a close and wide-ranging analysis of acting in film, I suggest to set off established cognitivist film theory (making meaning: inference and rhetoric in the interpretation of cinema) against recent phenomenological approaches (carnal thoughts and bodily knowledge: embodiment and moving image culture). In addition to the inspiring work of Vivian Sobchack and Pamela Robertson Wojcik, this article is considered to serve as a manual for further deepening and reflection on the topic.