Sensations of a Breakthrough Performance: Reese Witherspoon in Walk the Line

|

|

by Joerg Sternagel |

The Ring of Fire: Sensations of the art of American actress Reese Witherspoon in a leading role in James Mangold’s biopic Walk the Line from 2005: From the moment of her first appearance, Witherspoon’s academy-award winning portrait of the country singer June Carter Cash enables us to take part in a breakthrough performance, a performance closing up on the portrait of Johnny Cash by Joaquin Phoenix – we feel the chemistry between them, we watch them getting close. Following the life lines of Johnny Cash and June Carter, both director and leading actors show us more a complex love story of two celebrities than a detailed biography of the two famous country singers Cash and Carter – we take part in the display of the love of both protagonists‘ lives instead of being informed in detail about their daily and professional life. For a focus on connecting both lives, the script proposes to provide us with major lines of these lives in their thirties, highlighted in Cash’s highly-acclaimed concert at the Folsom Prison in California in 1968, he being 36, Carter 38 at that time. (1) It is the stress on these lines in the film that is supposed to attract our attention, even if there are sequences presenting us details of Cash’s childhood, his service at the army, and his early singing career. But, closing up on June Carter Cash again, on Reese Witherspoon’s portrait of her, what is it that makes us feeling moved, what notions, and what sensations do we get watching her performance, her breakthrough performance?

Within the Ring of Fire: Naturally, watching a film that is built upon its musical and sound track, that is focused on music and the life of musicians, there exists a temptation to reduce notions and sensations of a performance to the parts of the film where we see in this case: the actresse’s singing and performing on stage. We are then influenced by listening to the songs and watching the actress singing, moving and dancing on stage, communicating directly with the fictious audience in the film and indirectly with us before the screen. We may describe this process of taking part more easily by arguing with the notion and sensation of a musical experience that literally drags us in. So, this sensation seems to be the first and most obvious one when we want to analyze the experience with this film.

Wanting to describe the performance of Witherspoon off-stage seems to be

a more difficult task to fufill. This is why an analysis of her acting style

and our sensation with her performance, however, begins with the musical

experience we make. But, do we have a choice? Her first appearance in Walk

the Line is, after nearly half an hour of running time, not surprisingly,

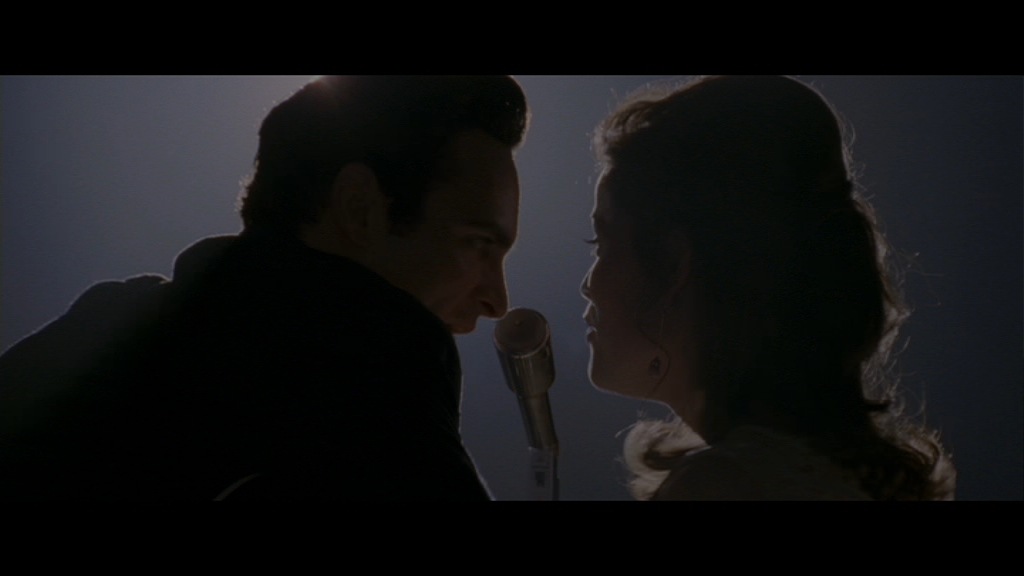

on and around stage where we are quickly dragged into the ring of fire by her,

and remain within it for the rest of the film:

(2)

[3] Sensations of a Breakthrough Performance: (Pre-) Influenced by the knowledge that both Reese Witherspoon and Joaquin Phoenix do credibly their own singing, we begin our experience of the main actresse’s performance while meeting the main actor: In their roles, Carter meets Cash around and on stage for the first time. (3) Supported by the musical introduction of these characters, we easily experience the enjoyment of what we watch. But, the sensation of Witherspoon’s performance implies more aspects we can describe and analyze. For this, we should try to keep in mind what Thomas Koebner, a German scholar in film studies, suggests: If we want to understand the lively impression we experience while watching a particular actor or actress, we will have to face the challenge of the exact description of the actor’s performance, we will have to work on a »mimography« of the actor or actress in question. Working on and with this mimography, we will eventually come to terms with the sensation of the particular performance. We will begin to realize this particular performance as a filmic element that creates meaning, and sensual as well as physiological effects. (4) In this way, we start to acknowledge performance and its senses in the first place without wanting to theorize it with the help of cognitivist and phenomenological approaches here in detail. In that way, picture this: We see Witherspoon, we watch her performance, and try to describe it, aiming at the wish to explain our sensation: Her (re-) creation of June Carter Cash, the daughter of a well-established country music family, appears to be completely determined by the conscientious use of a controlled body language that always includes an upright and honest posture. Her movements, gesture, and posture on- and offstage create the notion of a strong woman who is both in total control and full consciousness of her body. The camera follows her moves, and often closes up on her face, the most expressive part of her body in this character study: Her eyes are wide awake and full open, her lips are arching and demanding, her cheeks are assuring and commenting. Witherspoon acts in full use of her senses and thereby always offers well-balanced and well-placed notions of sense of humour, charm, and self-reflection:

»I’m not really much of a singer, John. I mean, I got a lot of personality. I got sass. I give it my all, but my sister Anita’s really the one who really got the pipes«. (5)

The overall awareness of such a bodily sureness creates the image of a woman who lives her life courageously and independently: a contrast to Phoenix’s (re-) creation of Johnny Cash who apparently is meant to live his life uncourageously and dependently. The actress, however, additionally manages to transfer this self-control and self-consciousness from her body language to her spoken language. The performance of her vocal intonation is mainly of a thoughtful and direct kind – taking part in the way of her character means to be involved into an extract of a study that displays (re-) action, and (self-) reflection: »Let’s go, time’s a-wastin‘«.

The sensation of Witherspoon’s performance in this film reflects the spectator’s awareness of the actresse’s material elements of her performance: Her vocal intonation, her facial expression, her posture. In consequence, this awareness of the material elements, as described above, enables us to come to terms with our sensation of this performance. Doing so, we are allowed to exclude every other aspect that influenced the final visualization of Witherspoon’s role and character. We exclude every possible aspect of the production and postproduction process that may have influnenced the performance, but that we are not able to see, feel, and experience. In this context, note the claim for the acknowledgement of the actor’s importance in an analysis of acting in film by the British film scholar Paul McDonald: »Analyzing film acting will only become a worthwile and necessary exercise if the signification of the actor can be seen to influence the meaning of film in some way. In other words, acting must be seen to count for something«. (6)

Aiming at an understanding of our sensation of performance, it does not help to exclusively stress the screenplay, the camerawork, the lighting, the mise-en-scène, the makeup, and the costume. The starting point must be to analyze the actor’s voice and body, the significance of both, »when the actions and gestures of the performer impart significant meanings about the relationship of the character to the narrative circumstances«. (7) Moving forward with such an approach to acting in film, it will also help to adjust to the suggestion of the American scholars in film studies, Cynthia Baron, Diane Carson, and Frank P. Tomasulo, again emphasizing on the above mentioned important starting point for understanding film performance:

... it is the actor’s voice that carry the paralinguistic features that create nuances of meaning in their intonations, inflections, rhythms, tone, and volume. Similarly, it is the bodies of actors that provide (at last the basis for) the facial expressions, gestures, postures, and various gaits film audiences encounter. (8)

Focussing on these elements, and scrutinizing the performance of Reese Witherspoon in this biopic, we learn a lot about our sensation of acting; we face the sensual and physiological effects that acting provides for us. So, closing up on June Carter Cash again, on Witherspoon’s portrait of her, what is it that makes us feeling moved, what notions, and what sensations do we get watching her performance, her breakthrough performance?

The relationship of her character to the narrative circumstances definitely comes clearer when we consider June Carter’s more and more mature behaviour while she waits for Johnny Cash to follow her, being drawn to this complex man. Suffering from two subsequent divorces, she manages to recover by expressing herself and her fear as well as implying Cash himself and his allure in the song »The Ring of Fire«: »Love is a burning thing and it makes a firery ring, bound by wild desire. I fell in to a ring of fire (...)« (9) Her sensuality, her sass, and her christianity help her within this ring of fire. Her artistic possibilites support her to move on. In the end, she falls for Cash who has finally caught up with her by the help of her: »The few comforts of his unhappy youth had come from the radio programs of June Carter, the luminous daughter of country music’s first family. When their paths cross, it’s her devotion and support that becomes his salvation«. (10)

We learn, that it is her personality that attracts Cash and that brings him back in line, that enables him to walk the line. The stress on these lines therefore attracts our attention, and the portrayal of June Carter Cash impresses us through its poise and vitality: The conscientious use of a controlled body language, the upright and honest posture, the movements and gestures create the notion of a performance that achieves the charcter study of a woman who is both in total control and in full consciousness of her body. Emotionally, the impact for us is the experience of a flow that constantly gains our attention and enables us to move on, too. We also move with the development of this character, with the experience of her going forward. The performance guides us to the sensation of a personal journey leading to a relief, to a breakthrough: We learn how two life lines initially begin as separate and finally come together.

The performance, indeed, imparts significant meanings about the relationship of the character to the other character. We read the performance to know what the character does and what the character feels. The displayed relationship of which we learn directly appeals to our senses.

[4] Outside the Ring of Fire: Having chosen the form of a sketch, this short description and introduction of how to deal with the sensation of the performance of a particular actress offers one possibility for a starting point. Watching a film always means to take part in performance. Choosing a performance that happens to be the most appealing, then means to explain its sensation. The technique of mimography, shortly presented here, helps to examine both performance and sensation. Such is the stress of the actor’s significance in and to film:

In Walk the Line, Reese Witherspoon draws to our attention from the beginning without losing it through the film. Excluding all technical and stylistic devices and circumstances, her performance alone gets us involved and leaves us fascinated, because it offers well-balanced and well-placed notions of sense of humour, charm, and self-reflection in all her appearances. These appearances of an actor’s performance do impress us as incidents, or, as Siegfried Kracauer points out: »The film actor’s performance ... impresses us as an incident – one of many possible incidents – of his character’s unstaged material existence. Only then is the life he renders truly cinematic«. (11) Kracauer stresses the physical aspects of film acting, and compares it to stage acting. Analyzing the film actor, he focuses on his emphasis of being, on his existence as a character. He questions the ontological status of film acting and explains its fundamental features.

Apart from the starting point of the analysis of the actor’s voice and body, these early approaches to film acting and its medium-related emphasis offer film and performance studies much: Rediscovering and reconsidering the film actor on a material and medium-related basis contribute to a better understanding of the medium itself and achieve another perspective in the analysis of spectatorship in film. The overall concept for a close and wide-ranging analysis of acting in film should be to thoroughly combine cognitivist film theory with phenomenological approaches. Casting the film actor in film criticism and studies illuminates the understanding of how performance create meaning, and how it appeals to our senses. Focussing on acting in film also offers insights into our active process to take part in a motion picture, to take part in the way of a character.

Taking part in the way of Reese Witherspoon‘s character means to be involved into an extract of a study that displays (re-) action, and (self-) reflection: June Carter Cash, that is what we finally learn from Reese Witherspoon, may not have been much of a singer, but may have got a lot of personality.